Age and Play

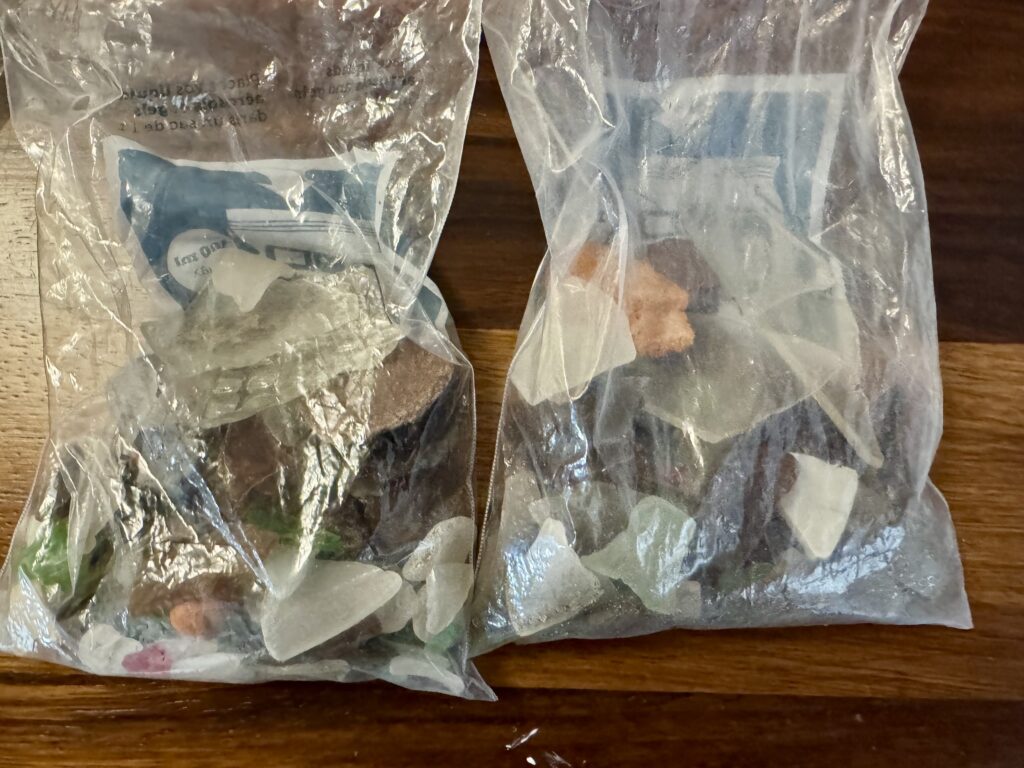

Playing in the Sand

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, 2026

The Sea Lions Know Something I Forgot

I am sixty years old, and I am learning to play.

This morning, I caught myself humming. No song. Just sound making itself because it wanted to. I stopped mid-hum and thought: when did I stop doing this? When did humming become something I had to notice rather than something that just happened?

And then yesterday. The sea lions.

Lions Playing on the Rocks

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, 2026

Hundreds of them off the coast of Loreto, leaping and spinning and riding waves with what looked like pure, uncomplicated joy. And here is what struck me: they were older. Many had grey muzzles. Scarred bodies. The marks of decades in the ocean. These were old sea lions. Experienced sea lions. Sea lions who had survived sharks and storms and whatever else the ocean throws at bodies over time.

And they were playing.

No different from young sea lions in their abandon. No careful moderation, no appropriate dignity. Just playing. Leaping. Spinning. Riding waves because riding waves feels good. Their age seemed irrelevant to the equation entirely.

I sat in the boat watching them, and something in my chest cracked open. Cracked, yes, but opened. Like a window that had been sealed shut for so long, I forgot windows could open, and suddenly there was air and light and the possibility of something beyond naming, but my body recognised immediately.

Star Sunshine

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, 2026

Alegría. Joy.

Joy unattached to happiness, contentment, or satisfaction with accomplishments. Joy. The kind that bubbles up from somewhere that has nothing to do with achievement, productivity, or being a responsible adult who takes life seriously.

The kind the sea lions have. The kind I seem to have misplaced somewhere between twenty and sixty. The kind I am just now realising I want back.

What I Learned About Growing Up

Somewhere along the way, I learned that growing up means growing serious.

I cannot point to the exact moment this lesson took hold. There was no single conversation or event. It was more like osmosis. The gradual absorption of cultural messages about what mature adults do and avoid. Adults work. Adults are responsible. Adults plan, achieve, and contribute. Adults avoid wasting time. Adults avoid play.

Or if they play, it is scheduled, optimised, and turned into another form of productivity. Exercise that counts as play. Hobbies that produce results. Social games that serve networking functions. Play with purpose. Play with outcomes. Play that justifies itself.

But what the sea lions were doing yesterday required no justification. It served no purpose I could identify. Exercise was incidental (though movement was involved). Socialising was incidental (though they played near each other). Skill practice was incidental (though the skills were evident). They were just… playing. For its own sake. Because it felt good. Because they were alive and the ocean was there, and their bodies knew how to move through it joyfully.

I watched them and thought, “I used to know how to do this.” I did. I remember childhood summers when entire afternoons disappeared into invented games that had no point beyond playing them. I remember the absorption. The timelessness. The way my body knew what to do without my mind directing it.

And then I grew up. And growing up meant putting that away. Meant learning that time is currency, that activities should have purpose, that joy without justification is frivolous, immature, something you outgrow.

Except the sea lions seem to have skipped entirely. The grey-muzzled, scarred, elderly sea lions seem to have missed any memo about dignity, seriousness, and age-appropriate behaviour. They are still playing. Still joyful. Still leaping.

And I am sitting here at sixty, realising: I got it wrong. The sea lions were right all along.

What the Research Says (And Why It Matters That I Am Reading It)

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, 2026

I am reading research on play and aging because that is what I do when I am trying to understand something. I read. I find frameworks. I look for explanations. This is probably part of why I lost play in the first place: I cannot just experience things. I have to understand them. Analyze them. Fit them into existing knowledge structures.

But the research is helping, so I am allowing it.

Brown and Vaughan (2009) argue that play is a lifelong human need, no mere developmental stage we pass through. They studied adults across the lifespan and found that people who maintain a capacity for play show better physical health, stronger social bonds, greater creativity, and more resilience when life gets difficult. The absence of play in adulthood belongs to suppression rather than natural maturation. It is suppression.

This word stopped me: suppression.

Something different from absence. From outgrowing. Suppression. Which implies something was there and was pushed down. Which implies it might still be there. Which implies it could be recovered.

I sat with this for a long time yesterday evening after the boat returned. Suppression. What suppressed my play? And the answer came quickly, almost too quickly, as though it had been waiting to be asked:

Everything. Work suppressed it. Poverty suppressed it. Precarity suppressed it. Chronic stress suppressed it. Cultural messages about what serious academics do suppressed it. Twenty-five years of contract work, where every moment had to be productive because any moment could be your last, suppressed it.

My play was buried alive under layers of survival necessity, cultural expectation, and internalised messages about what maturity demands.

But suppression is different from death. Suppression means it is still there. Somewhere. Under all those layers. Waiting.

The sea lions confirmed this. They looked nothing like they were working to play. They looked like playing was the most natural thing in the world. Which suggests that play is natural. Which suggests that the unnatural thing is the absence of play. Which suggests I have been living unnaturally for a very long time.

Qué alivio. What relief. To know it endures. Just suppressed. Just waiting.

Sea Lions Playing

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, 2026

The Neuroscience of Joy (Or: Why Play Eluded Me Even When I Wanted It)

Here is something I learned from Porges (2011) that changed how I understand the last five months, the last five years, possibly the last twenty-five years:

Play requires safety.

Something beyond cognitive understanding of safety. Beyond intellectual knowledge that you are probably fine. Physiological safety. The kind that the nervous system detects below conscious awareness through what Porges calls neuroception. The body is constantly scanning the environment, asking: Am I safe? Can I rest? Can I play?

And if the answer is no, the social engagement system goes offline. This is the neural pathway that supports play, connection, and spontaneous joy. When the nervous system is in threat mode (preparing to fight, to flee, to freeze), the social engagement system shuts down. You cannot access Play. Cannot feel lightness. Cannot allow the vulnerability that playfulness requires.

This is autonomic regulation, beyond choice. The body makes decisions about resource allocation below the level where consciousness operates.

For five months before I came here, my nervous system never registered safety long enough for play to become possible. I was in constant crisis mode. Waiting for calls. Waiting for bad news. Waiting for the next emergency. My body had no resources for playfulness, for vulnerability, for the energy expenditure that play requires when every resource must go toward threat management.

My nervous system chose for me. The choice to avoid play was never mine.

And reading this, understanding this, I felt something unexpected: compassion. For myself. For my body. For the twenty-five years before that, when contract work meant my nervous system never fully relaxed because security was always provisional, always temporary, always one crisis away from disappearing.

Of course play was unavailable to me. Of course, joy became impossible. Because my body was doing something very right rather than anything wrong: keeping me alive under conditions that offered no support for flourishing.

But here is what the research also says: nervous systems remain plastic across the lifespan. The capacity for play can be restored at any age if conditions support it. If safety can be established. If the threat can be interrupted. If the social engagement system can come back online.

I am sixty years old, and my nervous system is learning safety. And as it learns safety, play is beginning to return. Quietly, incrementally. In small signals: humming. Swimming for pleasure. Watching pelicans without needing to make it productive.

Small. But real. And growing.

Pequeños milagros. Small miracles. Pero milagros de todos modos. But miracles nonetheless.

What Play Looks Like When It First Returns

This morning, I walked in the water along the seashore.

This is a small thing. Maybe it seems like nothing. But for someone who has spent decades organising every activity around productivity, purpose, and outcomes, swimming because the water looks inviting feels revolutionary.

I got in. The cold shocked me like it does every morning. But instead of swimming laps, instead of counting strokes, instead of trying to improve my form, I just… moved. Followed curiosity about underwater rocks. Let my body do what feels good. Floated when floating felt right. Dove when diving felt right.

No plan. No goal. No timer.

And I realised: this is play. Unlike what I remember from childhood. Unlike what the sea lions do. My version. Sixty-year-old-woman-in-the-Sea-of-Cortez version. Modified. Tentative. Still learning. But real.

Guitard et al. (2005) studied play in older adults and found that play often looks different from childhood play but serves similar functions: engagement with novelty, absorption in the process rather than the outcome, pleasure for its own sake, and temporary suspension of everyday concerns. Older adults play through gardening, cooking, music, crafts, and exploration.

I am playing through swimming. Through humming. Through letting myself be curious about things without turning curiosity into research questions. Through allowing time to be unstructured. Through following impulses that have no justification beyond: this sounds good right now.

Small things. But they add up. Each one teaches my nervous system: it is safe to be spontaneous. Safe to follow pleasure. Safe to let go of control slightly and see what happens.

Each one is a tiny rebellion against the internalised voice that says: You are sixty years old, what are you doing? You should be serious. You should be productive. You should be concerned about declining capacities, limited time, and making every moment count.

Each one is a tiny agreement with the sea lions who say: no. Play. Leap. Spin. Your age is beside the point. Your joy is the point.

Estoy aprendiendo. I am learning.

Lentamente. Slowly.

Lero aprendiendo. But learning.

The Paradox That Makes Me Laugh

Here is something that makes me laugh now that I can laugh about it:

I am conducting research on rest and recovery and nervous system regulation. I am documenting how environmental conditions affect play capacity. I am reading literature on playfulness, aging, and successful life transitions.

I am turning the recovery of play into academic work.

This is very me. Very on-brand. Cannot just play. Have to study play. Have to document play. Have to theorise play. Have to turn play into scholarship because scholarship is how I make meaning, and scholarship carries legitimacy that pure experience often lacks in my mind.

But here is what I noticed yesterday watching the sea lions: they were documenting nothing. Reading no literature on play theory. Conducting no comparative analysis of their play behaviours across developmental stages. They were just playing.

And I thought: yes. That is the point. The point is to do it, first and foremost, with understanding secondary.

But I also thought: maybe both are okay. Maybe I can study, play, and also play.

Maybe the studying helps me trust that play is legitimate enough to allow.

Maybe the research gives me permission that my body needs before it can relax into playfulness.

Maybe there is no single right way to recover and play at sixty. Maybe scholarly-personal-narrative-researcher-trying-to-learn-to-be-playful-again is a valid way to do it.

The sea lions need no research to justify their play. But I might. At least for now. At least until my nervous system trusts playfulness enough to allow it without justification.

And maybe that is okay. Maybe that is my version. Nerdy. Academic. Needing frameworks before I can allow experience. But still moving toward the same place the sea lions are already inhabiting: joy. Lightness. Permission to leap.

Me río de mí misma. I laugh at myself.

What Sixty Knows That Twenty Could Barely Imagine

There is something sixty understands that twenty lacked the ground to know:

Nothing is permanent. Nothing is as high-stakes as it seems. Most of what feels catastrophic becomes a foundation. Failures leave you standing. Mistakes are survivable. The things you think will last forever dissolve. The things you think will destroy you become stories you tell.

At twenty, play was impossible because everything felt too important. Every choice felt permanent. Every failure felt existential. The stakes were always maximum.

At sixty I know better. I know that very little is as important as it seems. That most catastrophes become footnotes. That reputation is less fragile than fear suggests. That dignity survives embarrassment. That making mistakes carries no verdict on your worth.

This knowledge could support play. Could create psychological space where experimentation feels safe, where outcomes matter less than process, where I can be silly without it threatening my sense of self.

But knowledge alone falls short. The nervous system has to believe it. Has to feel safe enough to trust that playfulness leads somewhere other than catastrophe.This is the work I am doing. Teaching my sixty-year-old body what my sixty-year-old mind already knows: it is safe enough to play.

And here is what is helping: the sea lions.

When I skip for three steps, I am completely here. Future thoughts quiet. Past replays absent. Just: body moving, sun warm, this feels good.

That presence is what I lost. What chronic stress took from me. What I am reclaiming now, three steps at a time.

Volcanic Rocks

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker 2026

And here is what surprises me: it feels good. Beyond the skipping. The reclaiming. The gradual return of lightness. The sense that my body is becoming a place where joy is possible again.

For years, my body was a site of vigilance. Of tension. Of preparing for a threat. Now it is becoming something else. Something softer. Something more playful.

Mi cuerpo se está curando. My body is healing.

No sólo descansando. More than resting.

Curando. Healing.

Y parte de la curación es recordar cómo jugar. And part of healing is remembering how to play.

What the Sea Lions Teach About Successful Aging

Traditional models of successful aging emphasise maintaining function. Physical health. Cognitive capacity. Productivity. Contribution. (Rowe & Kahn, 1997).

But the sea lions suggest a different model.

Successful aging might be: maintaining the capacity for joy. For curiosity. For absorption in the present moment. For play.

Their bodies are older. Scarred. Slower now, less agile than young bodies. But they play anyway, through aging rather than despite it. Their play is a present-moment engagement, no effort to recapture youth. It is present-moment engagement with being alive in the body they have now.

This feels important.

Twenty again holds no appeal for me. No idealised version of youth calls to me. I want to be sixty and playful. Sixty and joyful. Sixty and capable of skipping for three steps when skipping feels right.

I want what the sea lions have: age that leaves joy intact. Experience that carries lightness alongside wisdom. Wisdom that includes lightness.

Henricks (2015) argues that play in later life serves a generative function: modelling joyful engagement for younger generations, resisting cultural narratives that equate aging with decline, and demonstrating that vitality persists across the lifespan.

If this is true, then learning to play at sixty is a contribution, no form of regression. It is resistance. It is saying: this is what aging can look like. Alive. Present. Joyful. Still learning. Still curious. Still capable of surprise. No grimness, no resignation, no decline toward inevitable loss.

The sea lions model this every day. I am trying to learn from them.

Slowly. With academic footnotes and self-consciousness they never carry. But learning.

And occasionally, when I forget to monitor myself, when I am absorbed in water or surprised by pelicans or simply here, I play.

Just for a moment. Just for three steps. Just for one spontaneous laugh.

But it is there. Real. Growing.

New Directions

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, 2026

Translation note. Spanish language passages were generated using Google Translate and subsequently reviewed and refined by the author. Any remaining infelicities reflect the limits of machine translation rather than intent.

References

Brown, S., & Vaughan, C. (2009). Play: How it shapes the brain, opens the imagination, and invigorates the soul. Avery.

Google. (n.d.). Google Translate. https://translate.google.com

Guitard, P., Ferland, F., & Dutil, É. (2005). Toward a better understanding of playfulness in adults. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health, 25(1), 9–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/153944920502500103

Henricks, T. S. (2015). Play and the human condition. University of Illinois Press.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. W. W. Norton & Company.

Rowe, J. W., & Kahn, R. L. (1997). Successful aging. The Gerontologist, 37(4), 433–440. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/37.4.433

Age and play in the same frame raises the question of what Brown (2010) calls the permission to be imperfect: the cultural prohibition on adult play is internalised most deeply in those whose worth has been contingent on productivity. Csikszentmihalyi (1990) identifies play as the purest form of autotelic experience — activity valuable in itself, not for any outcome. The bodily joy described in this entry is also a somatic signal of the nervous system's continued decompression: Porges (2011) notes that playfulness is a marker of ventral vagal engagement, a physiological state unavailable under chronic threat.