Alonetude represents a positive, integrated relationship with being alone, where one feels at home with oneself, regardless of physical company.

The concept of being alone typically occupies two opposing shores in our cultural imagination: the painful isolation of loneliness or the romanticised retreat of the solitary genius. During my thirty days by the Sea of Cortez, I sought a different territory, which I term alonetude. Alonetude represents a positive, integrated relationship with being alone, where one feels at home with oneself, regardless of physical company. This blog post explores alonetude’s methodology through the lens of Nash’s Scholarly Personal Narrative, a framework that bridges personal experience with scholarly rigour.

Keywords: alonetude, scholarly personal narrative, solitude, embodiment, autoethnography, qualitative inquiry, Sea of Cortez, third shore

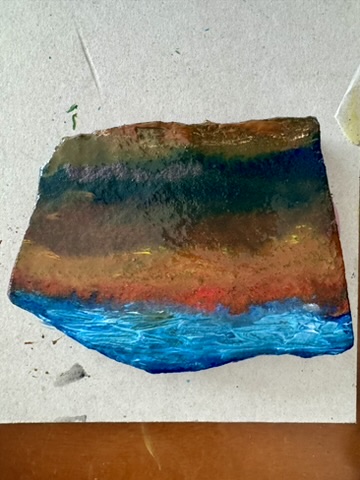

Title: Sediment of Memory

Artist Statement

This piece emerged through layering rather than planning. Pigment settled into the surface in ways beyond my full direction, forming bands that resemble horizon lines or sedimentary memory. What holds my attention is the tension between opacity and translucence. Some areas conceal, others reveal. Light moves differently across each stratum.

I notice how the colours echo landscape without replicating it. Water, shoreline, mineral, and sky appear as impressions rather than representations. The work becomes less about place itself and more about the body’s memory of place. How it registers colour, depth, and distance even in abstraction.

Within my broader creative inquiry, this piece sits alongside other material experiments where process becomes method. It reflects an ongoing engagement with layering as both artistic and epistemological practice. Meaning accumulates at the surface rather than being applied to it. It accumulates slowly, through contact, pressure, and time.

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, January 2026

The SPN Framework: Bridging Self and Scholarship

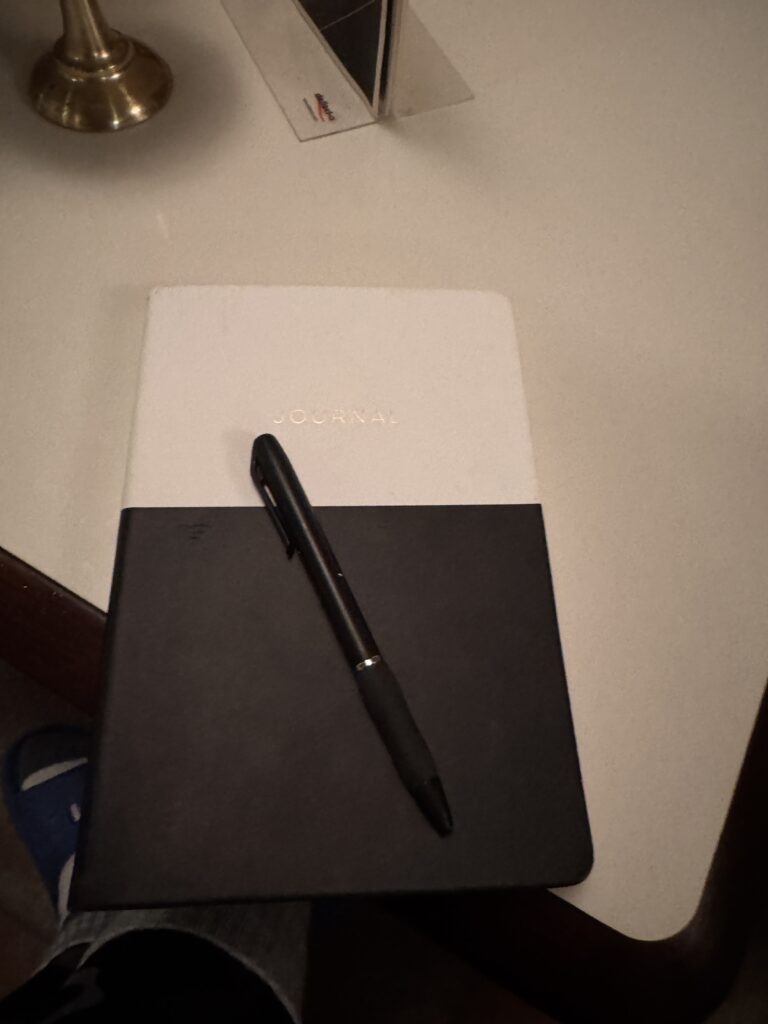

Title: Nothing Written

Artist Statement

This image sits at the threshold between experience and language. A journal closed. A pen resting diagonally across its surface. Nothing written yet, but everything present.

My work often returns to the moment before articulation, when thought is still somatic and unformed. In scholarly spaces, writing is framed as production. Here, writing is preparation. A readiness to listen inwardly before speaking outwardly.

The placement of the pen matters. It rests, ungripped, still. This resting signals consent rather than urgency. I write when something arrives. Force is absent from the process.

Within my broader inquiry into alonetude, journalling becomes a regulatory practice. A place where the body can settle into coherence before translating experience into theory. The closed cover holds privacy, safety, and containment. It reminds me that some insights are worthy of remaining inward, unreported, unperformed.

This photograph documents that pause. The space where reflection gathers strength before becoming language.

Photo Credit; Amy Tucker, January 2026

Scholarly Personal Narrative (SPN) provides a unique “third space” where analytical reasoning and personal authenticity intersect. Unlike traditional academic writing that demands detachment, SPN validates the researcher’s situatedness as a strength. This methodology treats lived experience as data, subjected to the same thematic synthesis as empirical materials. My inquiry into alonetude utilised a four-phase process:

- Pre-Search: I began by aligning my internal motivations with SPN’s methodological commitments, identifying the core thematic concern of intentional solitude.

- Me-Search: This phase involved a structured excavation of my own life, gathering raw fragments and vignettes from my time in Loreto to serve as the central field text.

- Re-Search: I moved toward deliberate engagement with existing scholarship, such as self-determination theory and polyvagal theory, to contextualise my emerging themes.

- We-Search: Finally, I translated my personal “I” into a collective “we,” offering thematic patterns and moral insights that resonate across varied life contexts.

Core Principles

The SPN methodology is operationalised through the VPAS model: vulnerability, perspective, action, and scholarly engagement (Nash, 2004). Each element informed my cultivation of alonetude.

Perspective transforms personal disclosure into something intelligible for an audience by embedding it in conceptual contexts. I framed my experiences against the “capacity to be alone,” a concept from Donald Winnicott (1958) that suggests aloneness is safe when one feels held by something larger. This interpretive layer ensures the narrative remains grounded in a broader human experience.

Vulnerability functions as an epistemic tool, enabling the writer to critically reinterpret moments of personal significance. In Loreto, this meant practicing self-interrogation and confronting the internal noise that surfaced when external distractions subsided. Vulnerability is selective; it serves the thematic throughline rather than standing as an isolated anecdote.

Action represents the translational moment where insights inform choices and behaviours. Cultivating alonetude required intentional shifts in practice, such as “mornings without performance” and “watching without comment.” These actions were enactments of meaning-making that altered my daily routines.

Scholarly engagement ensures that narrative meaning-making is intellectually valuable to the broader community. I integrated research on affective self-regulation to explain how volitional solitude supports well-being. This embeddedness enables individual trajectories to serve as sites for testing and expanding theory.

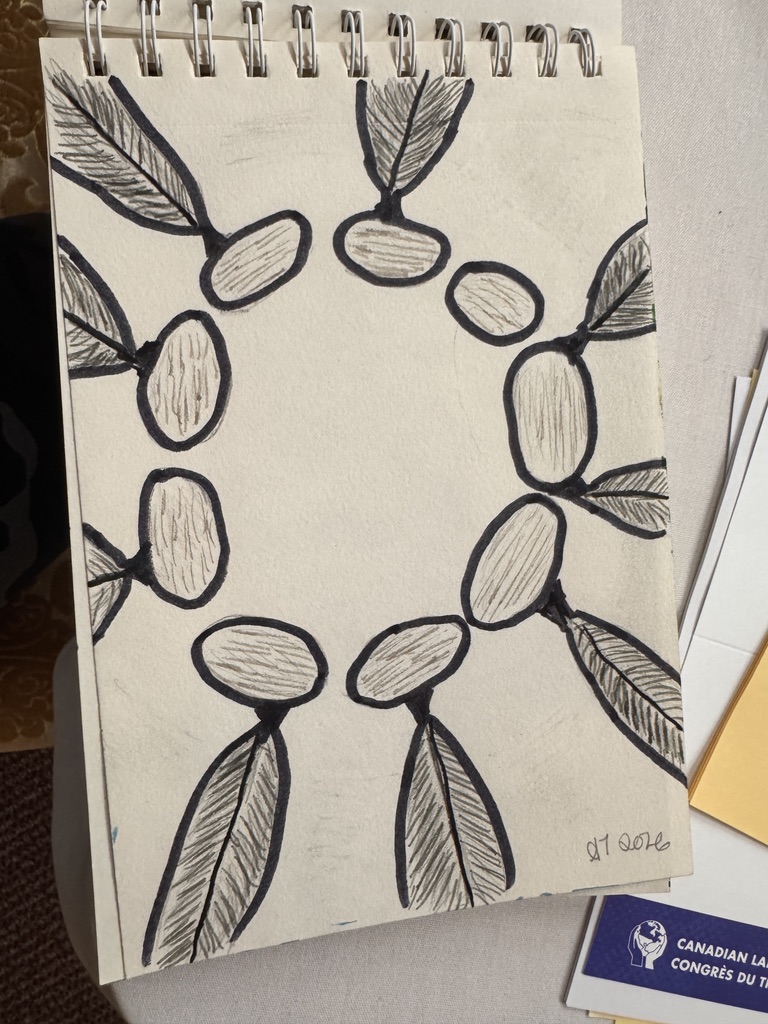

Title: The Circle of Witness

Artist Statement

This drawing emerges from my ongoing inquiry into relationality, witnessing, and the ethics of presence within alonetude. While solitude often carries connotations of separation, my work continues to reveal the opposite. Even in moments of intentional aloneness, I am held within circles of relation.

The figures in this piece are simplified, almost archetypal. Bodies reduced to gesture. Heads bowed or turned inward. Leaves extending from each form as though each figure is both human and ecological, person and landscape simultaneously. This merging reflects my broader research commitment to understanding identity as relational rather than individual.

The circular formation is deliberate. No figure leads. No figure dominates. Each occupies equal spatial ground, creating a visual field of mutual regard. The centre remains open, as possibility rather than absence. A space where listening gathers.

Within my methodological practice, drawing functions as a form of thinking. Line becomes language. Repetition becomes regulation. The slow rendering of each figure allows the nervous system to settle while insight surfaces without force.

This piece documents something other than isolation. It documents the felt sense of being surrounded by quiet forms of support that speak beyond language.

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, 2026

Reading the Body as Archive: A Counter-Archival Practice

A central pillar of my methodology involves reading the body as an archive. This concept positions the corporeal form as a repository of lived experience, challenging traditional archival paradigms that privilege textual documentation (Derrida, 1996).

By treating the body as a site of knowledge, I engaged in a counter-archival practice. This approach recognises that bodies retain past experiences, particularly traumatic or transformative ones, as implicit somatic memories (van der Kolk, 2014). My methodology utilised several tools to document this embodied archive:

- Somatic Logs: Documenting physiological and sensory shifts during the 30-day retreat.

- Visual Witnesses: Using photography to capture the “soft fascination” of the environment, which facilitates attention restoration (Kaplan, 1995).

- Intertextual Journals: Connecting scholarly reading to lived, felt experiences in real-time.

This framework is supported by Polyvagal Theory, which suggests that a state of felt safety, the ventral vagal state, is required to access these deep somatic archives (Porges, 2022). In the quiet of the Sea of Cortez, the absence of threat triggered the neuroception of safety, enabling a downregulation of defensive states and an opening of the embodied record.

The Portability of Alonetude

The ultimate goal of this methodology is universalizability: the capacity for a narrative to evoke recognition across contexts. Alonetude is a portable internal posture that remains available regardless of external circumstances. By employing the SPN and reading the body as an archive, researchers can bridge the gap between inner truth-telling and public knowledge-making. This process reveals that the home we seek is often found within ourselves, preserved in the very tissues of our being.

Title: Hydration, Paused

Artist Statement

This image sits within my ongoing visual inquiry into alonetude, embodiment, and the quiet rituals that sustain attention. My work turns away from spectacle. It turns instead toward ordinary moments where the body registers care before language has time to intervene.

A glass of mineral water, a slice of lime, condensation gathering along the surface. These are small events. Yet within them lives a form of restoration that is both sensory and relational. The body cools. The hand steadies. Time slows.

In my broader research, I examine how identity, labour, and precarity shape the nervous system’s orientation to rest. Here, relief is tactile. Visible. Measurable through droplets, temperature, and light.

This photograph participates in a methodology of noticing. It asks what becomes possible when attention is returned to the micro-gestures of care that make endurance sustainable.

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, January 2026

References

Derrida, J. (1996). Archive fever: A Freudian impression. University of Chicago Press.

Kaplan, S. (1995). The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15(3), 169–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-4944(95)90001-2

Nash, R. J. (2004). Liberating scholarly writing: The power of personal narrative. Teachers College Press.

Porges, S. W. (2022). Polyvagal theory: A science of safety. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 16, Article 871227. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnint.2022.871227

van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Viking.

Winnicott, D. W. (1958). The capacity to be alone. The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 39, 416–420.