What Was Found, What Was Made, What Remains

Concluding the Creative Thesis

30 Days by the Sea: A Research Inquiry into Alonetude

Amy Tucke

Master of Arts in Human Rights and Social Justice

Thompson Rivers University

Secwépemc Territory | Kamloops, British Columbia

March 1, 2026

“Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.” (Lorde, 1988, p. 131)

Keywords: alonetude, creative thesis, precarious academic labour, embodiment, human right to rest, scholarly personal narrative, somatic inquiry, arts-based research, healing, social justice

Part I: The Threshold Crossed

I went to Loreto for a reason I could barely articulate at the time. I had lost the capacity to feel the difference between exhaustion and living, and I needed to know whether that difference still existed.

After twenty-five years of precarious academic labour, contract work that renewed semester by semester, sometimes week by week, always with the implicit understanding that gratitude was the appropriate response to continued employment, I was laid off due to unstable enrolments. The termination arrived less as a single event than as the final gesture of a system that had been slowly extracting my health, my time, my creative energy, and my sense of worth for more than two decades. By the time it ended, my body had been keeping score for so long that I could no longer read the tally.

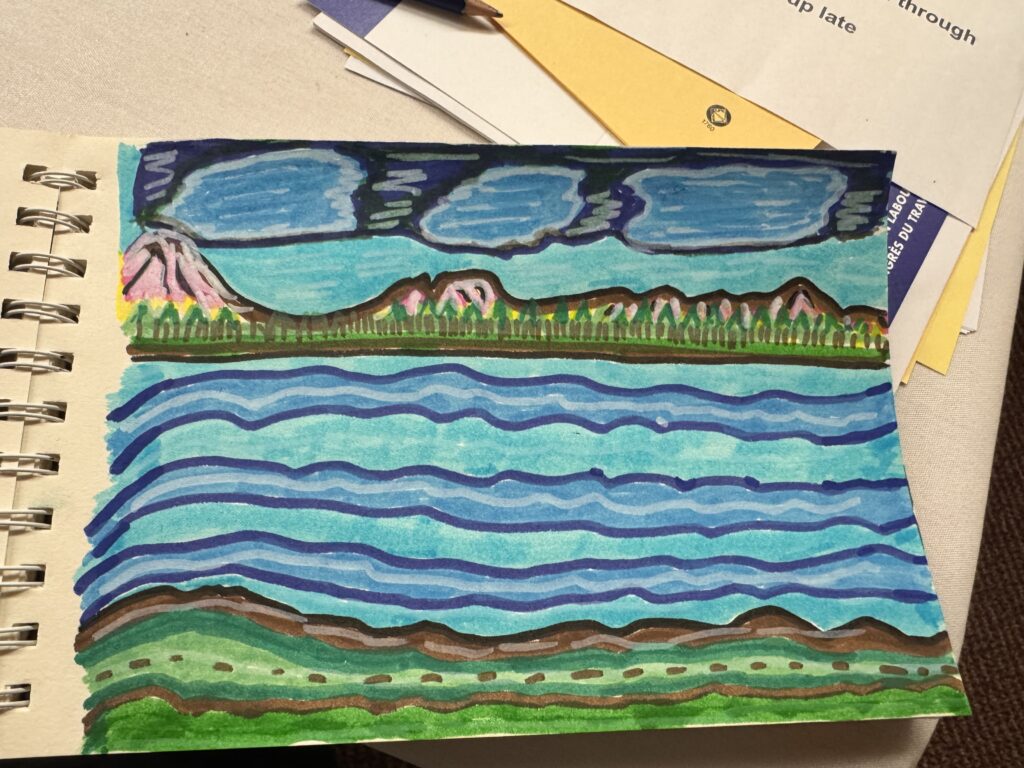

So I went to the sea. I went to Loreto, Baja California Sur, Mexico, a small town on the Sea of Cortez where desert mountains meet turquoise water, and pelicans dive without needing permission. I went alone. I stayed for thirty days. And I documented what happened when a woman who had spent her adult life performing competence, availability, and resilience finally stopped performing anything at all. I called this practice alonetude (defined in this study as intentional, embodied solitude practised as a method of healing, reflection, and critical inquiry), and I wrote about it every day on a blog called The Third Shore.

This document is the concluding chapter of that creative thesis. It gathers what was found, names what was made, and offers what remains, offered as reckoning rather than resolution. A reckoning with the body. With the institution. With the structures that produce exhaustion and then pathologise the exhausted. With what it means to heal in public, through scholarship and art, and to insist that the personal is more than political: it is methodological.

Aquí estoy. Here I am. Still.

What I Carried

I arrived in Loreto on January 1, 2026, carrying a suitcase, a camera, two books, Miriam Greenspan’s (2003) Healing Through the Dark Emotions and Brené Brown’s (2010) The Gifts of Imperfection, and a body that had forgotten how to rest without guilt. The body is, as Bessel van der Kolk (2014) argues, an archive. Mine held twenty-five years of contract uncertainty, of scanning inboxes for renewal notices, of performing wellness during semesters when depression had made getting dressed an act of will. My shoulders had been braced so long that I no longer noticed the bracing. My jaw ached from holding words I was unable to afford to say. My sleep had been fractured for years, my nervous system perpetually scanning for threat in the way that Stephen Porges (2011) describes as neuroception, the body’s unconscious assessment of safety or danger operating below conscious awareness.

I also carried grief. My adult son was deep in addiction, and I had been witnessing his disappearance, what Pauline Boss (1999) names ambiguous loss, the grief that arrives when someone is physically present but psychologically gone. My mother, eighty years old in Lethbridge, was declining slowly, and I was learning that midlife is the season when you parent in both directions simultaneously. I carried the accumulated weight of generational care.

And I carried a question that had been forming for months, a question I had yet to articulate fully but that Byung-Chul Han (2015) would later help me name: What happens when the structures meant to sustain us are the very structures producing our exhaustion?

This inquiry enters an established conversation about the value of solitude in intellectual and creative life. Paul Tillich (1963) explored how solitude functions less as absence than as presence, a condition in which the self becomes available to itself. More recently, scholars in contemplative studies have examined how sustained aloneness supports reflection, creativity, and moral discernment. Alonetude extends rather than borrows from this tradition by situating solitude within the specific conditions of precarious academic labour and by proposing that chosen solitude can function simultaneously as a personal healing practice, a methodological approach, and a structural critique.

What the Sea Received

Title: What the Sea Receives

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, January 2026

Artist Statement

The sky was rarely still. It moved in layers, cloud pulling against cloud, light shifting across the water in patterns that required nothing of the witness but attention. This photograph was taken on an early morning walk along the shore, the camera tilted upward as though the horizon itself had shifted. The Sea of Cortez stretches away at the left edge, mountains dissolving into haze at the far shore. What drew me was the asymmetry of the sky, the way the clouds gathered and thinned without effort or audience. Rachel and Stephen Kaplan (1989) describe this quality as soft fascination: the capacity of natural environments to hold attention gently, without cognitive demand, allowing depleted attentional resources to replenish. I stood here for a long time. The minutes went uncounted. That, too, was data.

The sea received all of it. Water is metaphorically healing, yes, but because the sea requires no performance. It holds no evaluation. The tide comes in regardless of whether you are productive or paralysed, published or precarious. The pelicans dive without concern for your curriculum vitae.

As described in the preceding artist statement, this soft fascination served as medicine. For thirty days, the Sea of Cortez offered it freely. I watched. I walked. I photographed. I wept. I wrote. And slowly, in increments so small they were sometimes invisible, my nervous system began to recalibrate.

Descansa, the sea seemed to say. Rest. And I did. And I wept. And both were holy.

A Note on Positionality

I am a white, settler, cisgender woman. I am a contract academic worker of twenty-five years, now completing a Master of Arts in Human Rights and Social Justice at Thompson Rivers University on Secwépemc Territory. I write from within the very conditions I am studying. My body has been a site of precarious labour and its aftermath. My experience of exhaustion, recovery, and alonetude is simultaneously my subject of inquiry and my method of knowing. I hold both the specific vulnerability of a contingent worker and the specific privilege of someone with the education, means, and mobility to spend thirty days by the sea. I name both because both are true, and because the scholarly personal narrative tradition (Nash, 2004) asks us to be accountable to the lived ground of our knowing.

Part II: Findings, What the Body Learned

This research documented a thirty-day solo retreat through daily written reflection, contemplative photography, and theoretical analysis, producing an integrated qualitative record of embodied experience. The thirty-day retreat unfolded in four distinct phases, each documented through daily blog entries that combined the Scholarly Personal Narrative methodology with contemplative photography, creative writing, and interdisciplinary theoretical engagement. The phases arrived without being planned in advance. They emerged, as qualitative data does, through the process of attending to what was actually happening rather than imposing a predetermined framework onto experience.

Robert Nash (2004) describes Scholarly Personal Narrative as a methodology that positions lived experience as legitimate scholarly data when properly theorised within academic frameworks. Nash (2004) often describes SPN as involving three interwoven voices operating simultaneously: the personal voice that speaks authentically from lived experience, the scholarly voice that contextualises experience within theoretical frameworks, and the universal voice that connects individual experience to broader human concerns. While related to autoethnographic traditions, this study adopts Nash’s Scholarly Personal Narrative framework, which explicitly integrates personal experience, theoretical analysis, and universal insight. This methodology guided every blog entry. What follows are the findings that emerged when those three voices were permitted to speak together across thirty days. The four phases that emerged from this documentation are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1

Four Phases of the Alonetude Retreat

| Phase | Days | Embodied Experience | Theoretical Framework |

| 1. Arrival and Disorientation | Days 1–7 | Guilt at stillness; body bracing against perceived threat; inability to rest without productive justification; scanning for danger in a safe environment; early photographs of weathered objects and thresholds | Polyvagal Theory (Porges, 2011); neuroception; attention restoration theory (Kaplan & Kaplan, 1989); liminality (Turner, 1969) |

| 2. Softening and Grief | Days 8–18 | Tears arriving unbidden; dreams returning; body softening; dark emotions emerging; grief for lost years surfacing once the nervous system registered safety; photographs of absence and shadows | Dark emotions (Greenspan, 2003); emotional alchemy; embodied trauma (van der Kolk, 2014); ambiguous loss (Boss, 1999); emotional labour (Hochschild, 1983) |

| 3. Clarity and Naming | Days 19–25 | Structural critique emerging from personal experience; naming precarity as a system rather than personal failing; refusing self-blame; photographs of gathering, arrangement, and quiet order; writing with increasing directness | Burnout society (Han, 2015); academic capitalism (Slaughter & Rhoades, 2004); situated knowledges (Haraway, 1988); radical rest as resistance (Hersey, 2022; Lorde, 1988) |

| 4. Integration and Departure | Days 26–31 | Carrying practice forward; alonetude as portable rather than place-dependent; colour returning to visual practice; goodbye as continuation; photographs of fragments in new context; return home to Harrison Hot Springs | Wholehearted living (Brown, 2010); contemplative photography (Karr & Wood, 2011); human rights integration (UDHR; ICESCR); self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000) |

Note. Phases emerged inductively from daily documentation rather than being imposed a priori. The transitions between phases were gradual rather than discrete, with considerable overlap between adjacent stages. UDHR = Universal Declaration of Human Rights. ICESCR = International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

Phase One: Arrival and Disorientation (Days 1–7)

The first week was the hardest. Less because anything felt wrong than because nothing was required of me, and I was uncertain how to inhabit that freedom. Twenty-five years of precarious academic labour had trained my nervous system to equate stillness with danger. When there was nothing to do, my body interpreted the lack of demand as a threat.

Porges (2011) explains this through the concept of neuroception, the autonomic nervous system’s below-conscious evaluation of environmental safety. In environments characterised by chronic uncertainty, the system defaults to sympathetic activation (the fight-or-flight response) or, when activation is unsustainable, to dorsal vagal shutdown (the freeze response characterised by numbness, disconnection, and the flat affect that can resemble depressive states). After decades of contract labour, where each semester brought the question of whether employment would continue, my neuroception had been calibrated to threat. Safety felt unfamiliar. Rest felt suspicious.

Title: Still Here

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, January 2026

Artist Statement

I photographed this piece of driftwood on Day 3, crouching low on the dark sand with the camera held close to the ground. What arrested me was beyond its shape, it wast its quality of having endured. The wood has been worked by time and water and shore into something that no longer resembles what it was, yet it holds together. The grain runs deep. The hollows where it was once punctured by something sharp have been smoothed rather than closed. It is beyond intact. It is beyond broken. It is here. Within the first phase of the retreat, when my nervous system was still scanning for threat and the guilt of stillness had yet to release, I was drawn repeatedly to objects shaped by forces outside their choosing and simply, quietly still. This image belongs to the category I came to call environmental witnesses: non-human elements that co-document the research by holding a quality the researcher needs to see.

I documented this in early blog entries through language that surprised me with its honesty. I wrote about the guilt that arrived when I sat without producing anything. I photographed weathered objects, worn shoes, abandoned bags, and driftwood arranged by no one, because these objects held the quality of having endured without performance. They had been shaped by time and elements rather than will. They were still here. They were enough.

Victor Turner (1969) describes liminality as the threshold state between what was and what will be, a space characterised by ambiguity, disorientation, and the dissolution of previous identity structures. The first week in Loreto was deeply liminal. I was no longer an instructor (the institution had ensured that), and still becoming whatever I was becoming, suspended between identities in a small town where no one knew my professional history and no one cared.

The shoreline became a metaphor and a method. Where desert met sea, where sand became water, where solid ground gave way to something that moved, these edges held the quality of my own transition. I began to call this space the third shore: beyond loneliness, beyond solitude, but the liminal territory between them where the labour of transformation occurs. The term third shore refers to the liminal space between loneliness and solitude, a conceptual terrain where imposed isolation can be transformed into chosen presence. In this thesis, the third shore functions both as a metaphor and as a methodological site, a place where personal narrative, visual practice, and structural analysis meet.

Title: The Third Shore

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, January 2026

Artist Statement

This is the photograph I had yet to know I was waiting to take. I was standing at the edge of the water on an early morning, shoes off, the dark volcanic sand cold beneath my feet, when the pelicans began to feed. They gathered in the middle distance, working the water together without urgency, the mountains of the far shore dissolving into haze above them. A single bird moved through the frame above, unhurried. I raised the camera and waited. The wave broke at my feet as the shutter opened. What is visible here is the thing the thesis is about: the exact line where desert sand becomes water, where standing ground gives way to something that moves, where one condition ends and another begins. This is the third shore. Victor Turner (1969) describes liminality as the space between what was and what will be. Here it is, in salt water and morning light. The pelicans, as I noted in early blog entries, dive without concern for your curriculum vitae. The tide comes in regardless of whether you are productive or paralysed. These are metaphors that arose from the natural environment rather than being imposednment; they were observations the environment offered freely to anyone willing to stand still long enough to receive them.

Phase Two: Softening and Grief (Days 8–18)

Around the eighth day, something shifted. My body, having spent a week registering the absence of institutional threat, began to soften. And with the softening came grief.

Title: The Door That Has Outlasted Its Institution

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, January 2026

Artist Statement

The Misión San Francisco Javier de Viggé-Biaundó was founded in 1699 and completed in 1758. It has been here for longer than Canada has existed as a country. Longer than the institution that employed me for twenty-five years. Longer than any of the administrative structures that decided, semester by semester, whether I would continue. I drove forty-five minutes into the Sierra de la Giganta on a dirt road to find it, and when I arrived, what arrested me was the quality of endurance rather than the grandeur. The rough rubble wall on the left has been losing its facing for centuries and is still standing. The carved stone around the doorway is still precise. The wood of the door is warm and worn and wholly present. The small figure in red at the left edge of the frame was a child crossing the plaza without any awareness of being documented. She will carry this morning differently than memory allows. The building will still be here when her grandchildren bring their grandchildren. This is what endurance without performance looks like at an architectural scale: beyond intact, beyond broken, simply here. Victor Turner (1969) describes the liminal state as the dissolution of previous identity structures. Standing in front of this door, in the second week of the retreat, I understood that what was dissolving in me had never been as solid as it seemed. The institution had offered the appearance of structure. This building offered the thing itself.

This was a demanding process. On Day 17, I was watching pelicans fish, and suddenly I was weeping, the kind of crying that starts somewhere below the ribs and moves through the whole body, the kind that makes you sit down because standing requires more structure than you currently have.

Miriam Greenspan (2003) names grief, fear, and despair as dark emotions, beyond negative: purposeful, carrying information the body needs us to know. She writes that the dark emotions become toxic through our strategies of avoiding rather than through their presenceidance: suppressing, denying, transcending prematurely, and escaping. The emotions themselves are neutral. Essential. Diagnostic. Greenspan offers a process she calls emotional alchemy, moving through seven steps: intention, affirmation, bodily sensation, contextualization, non-action, action, and transformation.

What I was grieving was complex. I was grieving the lost years, the decades spent overworking, taking on multiple contracts because I feared having none, trying to be everything for everyone while the institution offered nothing in return but the implication that I should be grateful for the opportunity. I was grieving what Arlie Hochschild (1983) calls the accumulated toll of emotional labour, the invisible work of managing feelings, performing wellness, maintaining the appearance of someone who was coping when coping had become its own full-time occupation.

Finalmente segura para sentir. Finally safe enough to feel.

Title: Presence Registered

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, January 2026

Artist Statement

I have never been comfortable with self-portraiture. The face in front of a camera performs; the shadow performs nothing. It is simply the mark of having been present: a body in light, documented through the absence of appearance rather than appearance itself light. This photograph was taken sometime in the second week, when the grief that had been building in the body began to surface. The sand is scattered with broken shells and small stones, the kind of shore that rewards slow attention. My shadow extends ahead of me, the camera visible in the raised right hand, the sandals improbably blue against the monochrome of the rest. What I notice now, looking at it, is how long the shadow is. How much space it takes. How completely it is just here. Within the research, I came to call this category shadow studies: self-documentation through mark rather than performance, presence registered without self-surveillance. This is what Donna Haraway (1988) means by situated knowledge: seeing from somewhere specific, from a body that casts a shadow on the ground.

The photographs from this phase documented absence: shadows on sand, empty doorways, objects at rest. The camera became what Ariella Azoulay (2008) describes as a civil instrument, one that witnesses conditions rather than producing beauty. Each image was a quiet refusal to look away from what had been endured.

Phase Three: Clarity and Naming (Days 19–25)

Once the grief had been met rather than avoided, something unexpected happened: clarity arrived. It was the clarity of better questions rather than settled answers. The question shifted from the one I had been asking myself for years, What is wrong with me?, to the one that structural analysis demands: What conditions produced this outcome, and who else is affected?

This shift is the central methodological commitment of the thesis. It is the inversion that transforms personal narrative into structural critique, that moves individual suffering from the domain of pathology to the domain of politics. Byung-Chul Han (2015) provides the theoretical architecture for this inversion through his concept of the burnout society, a society in which the imperative to achieve replaces external discipline with internal compulsion, producing subjects who exploit themselves more effectively than any external authority could. The achievement-subject, Han argues, is simultaneously a perpetrator and a victim, an exploiter and an exploited. The violence is auto-aggressive.

Guy Standing’s (2011) concept of the precariat, a new social class defined by chronic insecurity, lack of occupational identity, and truncated access to rights, gave me language for my structural position within the academy. I was far more than a contract worker; I was a member of a structurally produced class whose insecurity was functional rather than incidental, serving the institution’s need for flexible, disposable, and infinitely replaceable labour. Sheila Slaughter and Gary Rhoades (2004) name this system academic capitalism, the regime in which universities operate as market actors, treating knowledge and labour as commodities to be extracted rather than cultivated.

The blog entries from this phase became more direct. I named what had happened to me as structural harm rather than personal failure. I examined Erving Goffman’s (1959) distinction between frontstage performance and backstage reality, recognising how decades of performing competence and wellness had depleted the very resources those performances were designed to protect. I wrote about the invisibility of precarious academic work: the grading done at midnight, the courses prepared without compensation, the emotional labour of caring for students while the institution extended care to no one, least of all those doing the work.

Phase Four: Integration and Departure (Days 26–31)

The final phase was characterised by integration rather than resolution. Alonetude, I understood now, was a practice rather than a destination, portable, repeatable, available anywhere one was willing to turn toward oneself with intention and without judgment. On Day 27, I photographed in colour for the first time, departing from the black-and-white aesthetic that had defined the retreat. Colour arrived when I was ready to receive it. A flash of orange fruit. A red Volkswagen. Bougainvillea against a desert wall. Andy Karr and Michael Wood (2011) describe this in their work on contemplative photography, the practice of seeing with fresh perception, of receiving visual experience as it presents itself rather than imposing narrative upon it.

Title: The Colour That Arrived

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, January 2026

Artist Statement

On Day 27, I departed from the black-and-white aesthetic that had defined the retreat and began photographing in colour. The first colour image that mattered lay beyond the spectacular. It was this: a single fragment of red brick lying on dry earth, surrounded by pale gravel and small stones. The red is sudden and warm, the first warmth the visual record had admitted in nearly four weeks. I arrived at it beyond conscious choosing. I crouched near it because it was there, because the red registered in my body before my mind had decided anything. Andy Karr and Michael Wood (2011) describe contemplative photography as the practice of receiving visual experience as it presents itself rather than imposing narrative upon it. The brick received me before I received it. It holds a beauty beyond the conventional. It is damaged, irregular, slightly coffin-shaped if you are in a particular mood. But it is wholly, unapologetically red, and on Day 27, that colour was what the nervous system needed to confirm: something is returning. Something is warm.

On Day 28, I wrote about the quiet permission of invisibility, the discovery that being unseen in a small Mexican town, where no one knew my professional history, had allowed me to encounter myself without the armour of institutional identity. On Day 29, the shore began to speak: I photographed bricks embedded in sand, feathers after ascent, footprints being erased by tide, bone fragments that might be smiling. These images were the healing itself rather than illustrations of it. They were the healing itself, made visible through a methodology that treats art-making as a form of knowledge production (Leavy, 2015).

Title: Without Concern for Your Curriculum Vitae

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, January 2026

Artist Statement

I had been watching them for weeks before I captured them like this. Every morning they were there, working the water in the early light, and I photographed them from the shore at a distance that preserved their indifference. They never posed. They were never performing. They were simply doing what they do: diving, surfacing, diving again, completely absorbed in the fact of their own hunger and the abundance of the sea. What I kept returning to notice, across thirty days, was that their commitment to the work of being pelicans was absolute. They held no pause to evaluate whether today’s dive was as good as yesterday’s. They held no need to scan the shore for approval. On the day I photographed this, a group of perhaps sixty birds was working a school of fish near the surface, and the image that resulted is almost abstract: wings and water and the blur of concentrated, purposeful movement. Andy Karr and Michael Wood (2011) describe contemplative photography as the practice of receiving visual experience before interpreting it. What I received here, and what I return to when I need reminding, is this: the natural world requires no audience. It holds no evaluation. The pelicans dive without concern for your curriculum vitae, and in thirty days of watching them, I understood that this was the most useful thing I had ever been taught.

On Day 31, I said goodbye to Baja. On February 1, I arrived at Harrison Hot Springs, British Columbia, and practised alonetude in community, carrying the discipline of chosen presence into shared space. The practice had become what Brené Brown (2010) might recognise as an expression of wholehearted living: the willingness to be imperfect, to set boundaries, and to let go of who you thought you were supposed to be in order to become who you are. The evolution of the nervous system response across the retreat is documented in Table 2.

Title: Still Here (Harrison)

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, February 2026

Artist Statement

On February 1, the day after leaving Loreto, I stopped at Harrison Hot Springs, British Columbia, to practise alonetude in community before returning home to Kamloops. I was walking the lakeshore when this stump stopped me. It is massive, darkened by water and time, its root system exposed and reaching, its silhouette against the still lake holding the same quality I had been photographing for thirty days on the Sea of Cortez: endurance without performance. It is beyond intact. It is beyond broken. It is here. I understood, crouching by the water to photograph it, that this was the thesis proving itself. The practice had traveled. The attention I had trained in Loreto, the capacity to be stopped by worn things, to find in darkened wood and still water the quality of having-been-through-something-and-remained, had come with me. This is the companion image to Still Here, made on the dark volcanic sand in Loreto on Day 3. Those two photographs, one from a Mexican sea and one from a British Columbia lake, are the same photograph. Same quality of attention. Same subject. Different shore. Alonetude, I wrote on the final day of the retreat, requires no thirty days or a retreat in Mexico. It requires intentionality, presence, and the willingness to turn toward oneself without judgment. This stump is the evidence.

Table 2

Nervous System Transitions Across the Retreat

| Polyvagal State | Retreat Phase | Embodied Indicators | Photographic Register |

| Involuntary weeping, fatigue, deep sleep, appetite changes, and dreams returning | Phase 1: Arrival | Braced shoulders, clenched jaw, fractured sleep, guilt at rest, scanning | Weathered objects, harsh contrast, thresholds, fixed frame perspectives |

| Dorsal vagal (freeze/grief) | Phase 2: Softening | Involuntary weeping, fatigue, deep sleep, appetite changes, dreams returning | Shadows, absences, empty spaces, under-exposure, blur, ground-level |

| Emerging ventral vagal (safety/connection) | Phase 3: Clarity | Steady breathing, released jaw, clearer thinking, capacity for structural analysis | Gathered objects, arrangements, quiet order, clearer compositions |

| Ventral vagal (social engagement) | Phase 4: Integration | Softened expression, laughter returning, capacity for colour, readiness for community | Colour photography, found colour, playful compositions, environmental witnesses |

Note. Polyvagal states are described as documented through Scholarly Personal Narrative methodology, based on Porges (2011). States are dynamic and overlapping rather than discrete categoriesing processes. Photographic register describes the predominant visual qualities of images produced during each phase, functioning as embodied data within arts-based research methodology (Leavy, 2015).

Part III: Reflections, The Researcher as Subject

On Methodology as Medicine

Healing was beyond what I expected the methodology to do. I expected it to document. But Scholarly Personal Narrative does something that more detached methods cannot: it requires you to stay in your own experience rather than hovering above it with analytical distance. Nash (2004) insists that the researcher acknowledge their positioning rather than hiding behind passive constructions that imply objectivity. This insistence, stay in your body, write from where you are, resist pretending you are nowhere, turned out to be therapeutic in the deepest sense.

Donna Haraway (1988) describes this as the refusal of what she calls the god trick, the pretence of seeing everything from nowhere, the disembodied gaze that claims universality by erasing its own location. Haraway argues for situated knowledges: partial, accountable, embodied perspectives that gain their authority from within the partial rather than from the claim to see everything the honesty of acknowledging what they see from where they stand. My thirty days by the sea provided knowledge in its purest form. I could only see from the shore I stood on. And that was enough.

On What Arrived Without Being Planned

None of the most important findings were anticipated. Weeping on Day 17 while watching pelicans arrived beyond planning. Colour on Day 27 arrived beyond planning. The question inverting itself from personal pathology to structural critique. These emergences are precisely what qualitative methodology is designed to honour, the recognition that the most significant data often arrives unbidden, in the spaces between intention and attention. Following the retreat, the daily blog entries were reviewed as a chronological research journal and interpreted thematically, with patterns and phases identified through repeated reading of the complete record.

Patricia Leavy (2015) argues that arts-based research generates knowledge unavailable through conventional methods precisely because artistic processes engage perception, intuition, and embodied knowing alongside analytical reasoning. The camera reached beyond mere recording of what I saw; it revealed what I was yet to say in words. The blog reached beyond documenting what happened; it producedd understanding in the act of writing. Method became medicine because the method required presence, and presence is what trauma steals.

On Positionality and Privilege

I must name what is true about my position. I am a white, cisgender, settler woman who had enough resources to spend thirty days in Mexico healing from institutional harm. Indigenous peoples on the very land where I live, Secwépemc Territory, may lack such mobility options while navigating compounded harms of colonial dispossession, environmental racism, and institutional exclusion. Precariously positioned Mexicans in Loreto may serve tourists like me while carrying their own invisible burdens.

Linda Tuhiwai Smith (2012) warns against research practices that take from communities without reciprocity. While this autoethnographic work focuses on my own experience, it must contribute to broader conversations about labour rights, institutional accountability, and collective healing rather than centring individual self-improvement divorced from structural change. My solitude was chosen. Many people’s isolation is imposed. The distinction matters enormously, and this thesis refuses to collapse them into a single category. Alonetude names the labour of transforming imposed aloneness into chosen presence, but the fact that such labour is necessary is itself an indictment of the structures that produced the imposition.

This research reflects the perspective of a single researcher and is shaped by particular social, geographic, and institutional conditions that remain unshared universally. These constraints are part of the situated knowledge this work produces rather than limitations that undermine it, but they should be held in view as readers consider how these findings might speak to experiences beyond this one.

Title: Situated at the Edge

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, January 2026

Artist Statement

This photograph was made at Harrison It was made at Harrison Hot Springs, British Columbia, on February 1, the day after I left the Sea of Cortez, when I stopped to practise alonetude in community before returning home to Kamloops. The water is almost still, reflecting the pale sky and the sedge grass at the far bank. My shadow extends ahead of me, long and thin, reaching toward the reflection of the world. I include it here, in the positionality section, because it holds something this section requires: the image of a researcher at the edge of her own territory, neither inside nor outside the frame, present without being centred. Donna Haraway (1988) calls this situated knowledge, the understanding that all knowing comes from somewhere, from a body standing somewhere specific, casting a shadow in a particular direction. This shadow points outward, toward water, toward sky, toward the reflected world. It persists within the image. It is the image.

Part IV: A Human Rights Reckoning

From Personal Pathology to Structural Critique

The most important finding of this thesis reaches beyond solitude. It is about the inversion, the moment when the question shifts from “What is wrong with me?” to “What conditions produced this outcome, and who else is affected?”

This inversion is the methodological heart of human rights inquiry. Human rights frameworks ask far more than for individuals to heal themselves from structural violence. They ask structures to account for the harm they produce. When a worker collapses from exhaustion, the human rights question reaches beyond whether they should have practised better self-care but whether the conditions of their employment violated their fundamental rights to health, rest, and dignified labour.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR; United Nations, 1948) establishes in Article 1 that all human beings are born free and equal in dignity. Article 23 affirms the right to just and favourable conditions of work. Article 24 establishes the right to rest and leisure, including reasonable limitation of working hours. Article 25 guarantees the right to a standard of living adequate for health and well-being.

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR; United Nations, 1966) operationalises these declarations through binding obligations. Article 7 requires just and favourable conditions of work, including safe and healthy working conditions and reasonable limitation of working hours. Article 9 establishes the right to social security. Article 12 recognises the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.

My experience, twenty-five years of precarious academic employment culminating in occupational burnout, depression, and institutional termination, is far more than a personal narrative. Read through the lens of international human rights law, it may constitute a pattern consistent with potential violations of labour and health rights, requiring structural remedy. Table 3 maps these conditions against the relevant international human rights instruments.

Table 3

Human Rights Violations in Precarious Academic Labour

| Right Violated | Legal Source | How Violated | Evidence from Retreat |

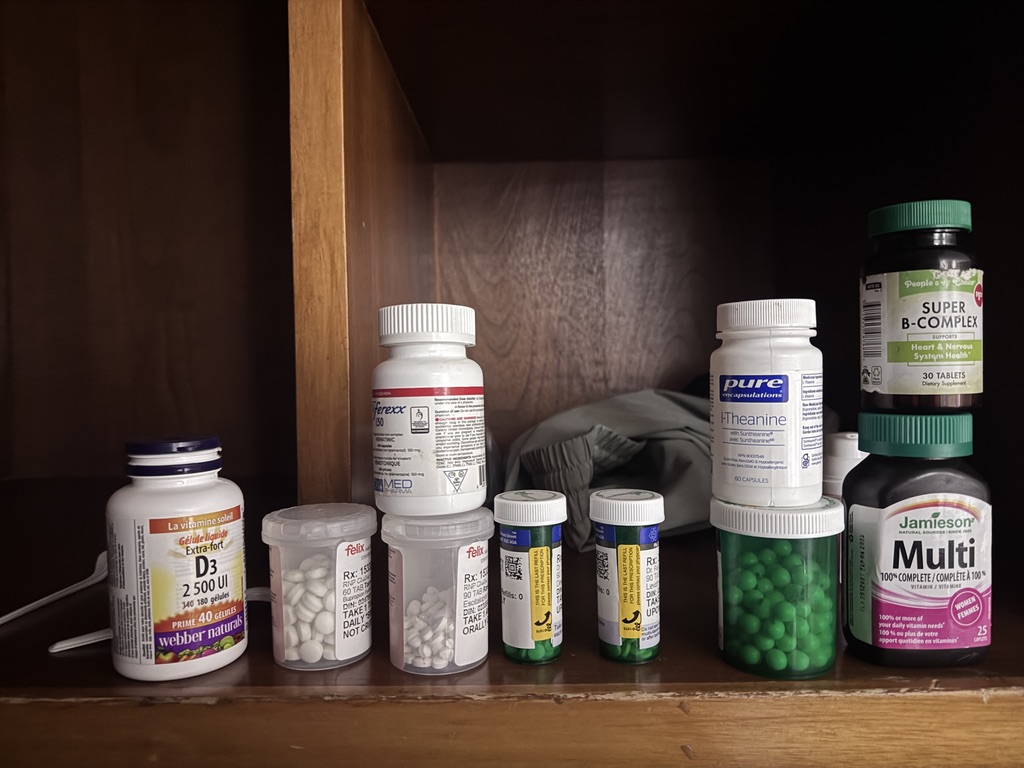

| Right to health (including mental health) | ICESCR Article 12; WHO Constitution | Chronic stress, burnout, depression produced by insecure employment; occupational trauma unrecognised as workplace injury | Body bracing documented in Phase 1; weeping in Phase 2 indicating stored somatic trauma; depression worsening requiring medication adjustment |

| Right to rest and leisure | UDHR Article 24; ICESCR Article 7 | Constant availability expected; rest experienced as guilt; boundaries punished through non-renewal of contracts | Guilt at stillness in Phase 1; inability to rest without productive justification; seventeen days required before nervous system registered safety |

| Right to decent work | ICESCR Article 7; ILO Decent Work Agenda | Precarious contracts without job security, benefits, or occupational identity; labour extracted without reciprocal institutional obligation | Structural critique emerging in Phase 3; naming precarity as system failure; recognising that gratitude was demanded in exchange for exploitation |

| Right to dignity | UDHR Article 1; ICCPR Preamble | Institutional disposability; treatment as extractable resource; termination after decades of service | Phase 4 integration: refusing to internalise disposability as personal failure; reclaiming worth beyond institutional validation |

| Right to social security | ICESCR Article 9; UDHR Article 22 | Contract labour excludes access to employment insurance, stable pension, benefits; structural vulnerability by design | Contract labour excludes access to employment insurance, a stable pension, benefits, and structural vulnerability by design |

Note. ICESCR = International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (United Nations, 1966). UDHR = Universal Declaration of Human Rights (United Nations, 1948). ICCPR = International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (United Nations, 1966). ILO = International Labour Organization. WHO = World Health Organization. These frameworks establish that the conditions described in this thesis constitute potential human rights violations requiring structural remedies rather than individual coping strategies.

The Structural Inversion

The following table presents the central inversion of this thesis, the reframing that occurs when individual experience is read through structural analysis rather than personal pathology.

Table 4

The Structural Inversion: From Personal Pathology to Systemic Analysis

| Dominant Framing (Personal Pathology) | Structural Reframing (Human Rights Analysis) |

| “She burned out because of her workload” | The workload was structurally unsustainable; burnout is an institutional outcome rather than a personal failure (Han, 2015) |

| “She should have set better boundaries.” | Boundaries are punished in precarious employment through non-renewal; the demand for boundarylessness is structural violence (Standing, 2011) |

| “She needed therapy for her depression” | The depression was occupationally produced; the remedy is structural change alongside individual treatment (van der Kolk, 2014) |

| “She chose to go on retreat, that is self-care” | The retreat was necessitated by institutional harm; rest should exist beyond requiring private funding and personal crisis to access (ICESCR Article 7) |

| Resilience narratives individualise structural problems; the question is why individuals must endure rather than whether they canrance is required (Berlant, 2011) | Resilience narratives individualise structural problems; the question is why individuals must endure rather than whether they canrance is required (Berlant, 2011) |

| “She should be grateful for the opportunities she had” | Gratitude cannot be demanded in exchange for rights violations; exploitation holds no benignity through the expectation of thankfulness (Hochschild, 1983) |

Note. This table illustrates the central analytical move of the thesis: reframing individual experience within structural critique. Each dominant framing locates the problem within the individual; each structural reframing locates the problem within institutional systems and policy failures. The inversion holds personal agency intact but refuses to let structural accountability be displaced onto individual coping.

Part V: Key Learnings

What This Research Taught Me

Table 5

Ten Key Learnings from the Alonetude Retreat

| Learning | Explanation and Theoretical Grounding |

| 1. The body is an archive. | Van der Kolk (2014) argues that trauma is stored in the body, in braced muscles, fractured sleep, and chronic activation. This thesis confirms that the body is also an archive of institutional harm, holding the cumulative weight of structural conditions that official records leave unnamed. My body had registered what had happened to me long before my mind could articulate it. |

| 2. Rest is a human right rather than a reward. | Article 24 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (United Nations, 1948) establishes the right to rest and leisure, unconditionally, regardless of productivity, performance, or institutional approval. When rest requires private funding and personal crisis to access, the system has failed. |

| 3. Grief is diagnostic. | Greenspan (2003) teaches that dark emotions carry information. The grief that surfaced on Day 17 was evidence of truth rather than weakness; it was the body’s truthful account of what had been lost. Grief for the years spent overworking, for the relationships deferred, for the creative life deferred, this grief was evidence of harm, as legitimate as any clinical assessment. |

| 4. The question must invert. | The most significant shift in the retreat was the inversion from “What is wrong with me?” to “What conditions produced this?” This is the essential move of human rights inquiry: locating the problem in structures rather than individuals, in policy rather than personality. |

| 5. Alonetude is labour. | Choosing to be alone, staying with discomfort, transforming imposed isolation into generative solitude, this is work. It requires intentionality, courage, and the material conditions (time, space, safety) that are themselves structurally distributed. Alonetude is active identity work rather than passive withdrawalrk. |

| 6. Art makes knowledge that words cannot. | Patricia Leavy (2015) argues that arts-based research generates knowledge unavailable through conventional methods because artistic processes engage perception, intuition, and embodied knowing alongside analytical reasoning. The photographs in this thesis said things the written entries could only approach. Contemplative photography, painting, and found-object work produced findings that propositional language alone could carry only partially. Art is a research method, and its data is real. |

| 7. Healing is beyond the the individual’s responsibility alone. | When harm is structurally produced, healing must be structurally supported. Privatising recovery, expecting individuals to heal themselves from institutional violence using their own resources, is itself a form of structural violence. The retreat I undertook was necessitated by institutional harm and funded through personal savings. That arrangement should be understood as a symptom of structural failure, and as an argument for collective institutional remedies. |

| 8. Seeing slowly is a methodology. | Contemplative photography, as practised in this thesis, concerns the training of attention rather than the production of beautiful images. It is about learning to receive visual experience before interpreting it, about allowing the world to present itself on its own terms. This discipline of perception is transferable to all forms of inquiry and constitutes a research method in its own right. |

| 9. The personal is methodological. | Scholarly Personal Narrative methodology (Nash, 2004) insists that personal experience, properly theorised, constitutes legitimate scholarly data. This thesis demonstrates that the I in research carries analytical weight. The voice that says I was exhausted, I was laid off due to unstable enrolments, I went to the sea is also the voice that reads Porges, cites Standing, and analyses human rights law. The personal is the methodology, and the methodology is the scholarship. |

| 10. The practice is portable. | Alonetude requires intentionality, presence, and the willingness to turn toward oneself without judgment. It can happen in five minutes on a park bench or in a quiet room after the children have gone to school. Thirty days in Mexico made the practice visible; the practice itself travels wherever the practitioner travels. It asks only for attention. |

Note. These learnings emerged inductively from thirty days of daily documentation using Scholarly Personal Narrative methodology (Nash, 2004), contemplative photography, and interdisciplinary theoretical engagement. They represent the primary findings of this creative thesis.

What Alonetude Is and Is Beyond

Table 6

Alonetude: Clarifying the Concept

| Alonetude IS | Alonetude IS BEYOND |

| Both embodied practice and a critical analytic lens | Loneliness rebranded with a gentler name |

| The labour of transforming imposed aloneness into chosen presence | Passive withdrawal or avoidance of difficulty |

| Both embodied practice and critical analytic lens | A self-help technique divorced from structural analysis |

| Situated within institutional and political architectures that produce separation | An individual coping strategy that excuses institutions from accountability |

| Accessible through four typologies: restorative, creative, political, and ceremonial | A single, fixed practice with prescribed steps |

| Portable, adaptable, available in five minutes or thirty days | Requiring a retreat, financial resources, or geographic relocation |

| A rights-bearing practice grounded in the right to rest, health, and dignity | A luxury available only to those with privilege |

Note. Alonetude is the original theoretical framework introduced by this thesis. The four typologies, restorative, creative, political, and ceremonial, are described in the thesis and are complementary rather than mutually exclusive.

Part VI: Artist Statement

Seeing Slowly: Photography and Visual Art as Research Methodology

Ariella Azoulay (2008) argues that the camera reaches beyond a mechanical device for producing images but a civil instrument for negotiating relations between people and their conditions.

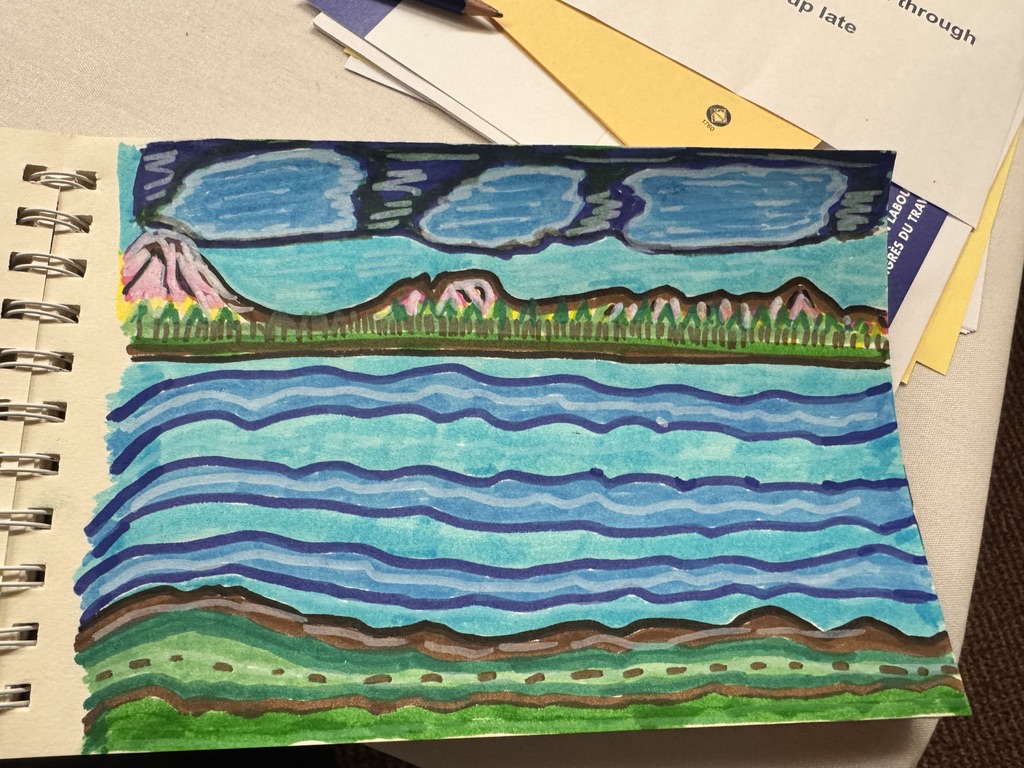

In this study, photographs and artworks function as primary research rather than illustrations data within an arts-based methodology. This thesis treats visual art, photography, drawing, watercolour, painted stones, mixed-media assemblage, and found-object work as a form of scholarly argument rather than an illustration but as a primary mode of knowledge production. Every image in The Third Shore blog is research data. Every painted stone is a finding. Every photograph of a shadow on sand, a worn shoe, or an empty doorway constitutes evidence within an arts-based research methodology that recognises what words alone cannot capture. The visual materials were organised chronologically alongside the daily written entries and revisited during the analysis stage to identify recurring motifs, transitions, and emergent themes.

On the Photographic Practice

The photographic practice developed during the retreat is characterised by deliberate imperfection. I shoot primarily in black and white, employing high- and low-contrast, minimalist compositions, intentional under- and over-exposure, blur, grain, fixed-frame perspectives, and ground-level handheld techniques. These are methodological choices rather than aesthetic failuresal choices. Each technical decision serves a purpose within the research inquiry.

High contrast serves the thesis because the experience being documented is one of extremes, the sharp edges between institutional performance and private collapse, between exhaustion and emerging rest. Blur serves the thesis because some experiences resist clarity, and the attempt to render everything in sharp focus is itself a form of violence against the imprecise, provisional quality of healing. Ground-level perspectives serve the thesis because the researcher’s position during much of the retreat was literally low, sitting on rocks, crouching by the waterline, lying on sand, and the camera should document from where the body actually was rather than from the elevated position of an observer who stands above experience.

Sarah Pink (2013) argues that visual research methods must attend to the sensory, embodied dimensions of experience rather than treating images as mere records of what was seen. My photography practices what Pink calls sensory ethnography, an approach that attends to how seeing, hearing, touching, and moving create knowledge. The camera is an extension of the body rather than separate from itn of the body’s attention, pointing where the nervous system directs it, pausing where the breath pauses, holding still when stillness arrives.

On Subject Matter

I arrived in Loreto without a shot list. I arrived with a camera and a body that had forgotten how to rest, and the subjects found me before I found them. What I photographed across thirty days was received rather than chosen, the way a driftwood piece arrests you mid-stride, the way a shadow falling across wet sand demands that you stop and look. This responsiveness is entirely intentional. It is the point.

The subjects that recurred throughout the retreat shared a quality I came to recognise as endurance without performance. Worn objects. Threshold spaces. Things shaped by forces outside their choosing that were, nonetheless, still here. A piece of driftwood smoothed by decades of tide and sand. An abandoned structure behind a rusted fence, its walls intact, its institution gone. A spent half-citrus on dark stones, its geometry still legible even after everything extractable had been taken. I was drawn to these subjects precisely because of their ordinariness it. They were doing nothing for the camera. They were simply present. And presence, I was learning, was the practice.

There is a particular challenge in photographing stillness when you have spent your adult life in motion. The academic precariat persists. It holds no luxury of stopping. You teach while grieving, grade while ill, prepare courses that may never be offered again, perform enthusiasm for institutional initiatives unlikely to survive the next budget cycle. The body becomes accustomed to perpetual forward movement, to the posture of someone who is always almost catching up. To stop and look at a stone, to crouch in the sand and wait for the light to shift, to spend twenty minutes photographing the way a feather rests against gravel; this is an act of resistance that the body resists before the mind can name it. The first week, I photographed quickly. I was efficient. I had somewhere to be, though I had nowhere to be. By the second week, I was beginning to slow. By the third, I understood that the slowing was the subject.

Wang and Burris (1997) developed Photovoice as a participatory research methodology in which people use cameras to document their lived realities and bring those realities into conversation with broader social analysis. While this thesis is autoethnographic rather than participatory in the traditional sense, it draws on Photovoice’s central commitment: that the person who experiences a condition is also the person best positioned to document it. My camera shared my experience rather than translating it for an outside audience. It participated in the experience itself, shaping what I noticed, directing where I crouched and waited, insisting that I remain in contact with the physical world when the easier option was retreat into abstraction.

The non-human world proved to be an unexpectedly generous research collaborator. Pelicans, as I noted in early blog entries, dive without concern for your curriculum vitae. The tide comes in regardless of whether you are productive or paralysed. These were metaphors that arose from the natural environmentnment; they were observations the environment offered freely to anyone willing to sit still long enough to receive them. Rachel and Stephen Kaplan’s (1989) concept of soft fascination (the capacity of natural environments to hold attention gently, without cognitive demand, allowing depleted attentional resources to replenish) describes precisely what I experienced when I stopped trying to photograph something significant and simply began attending to what was there: the way light moved across the Sea of Cortez at six in the morning, the arrangement of stones someone had made and left without signature, the blue of a sea-tumbled glass fragment resting in pale gravel as though it had always been there and had never needed to be anywhere else.

I want to say something honest about self-portraiture, because it is the category that surprised me most. I have always found my own face an uncomfortable subject. The face performs. It knows it is being watched and arranges itself accordingly. But the shadow performs nothing. A shadow is simply the mark of having been present: a body in light, documented through the absence rather than through appearancee of light. When I began photographing my shadow on the sand, I understood that this was the closest I could come to honest self-documentation, the researcher present in the frame without the researcher having to manage the frame. Donna Haraway (1988) argues that all knowledge is situated, that every act of seeing comes from somewhere, from a body standing in a specific place, casting a shadow in a particular direction. The shadow studies that emerged throughout the retreat arose from intentional positioning rather than camera shyness. They were a methodological commitment: I am here, I am looking, and here is the proof of my location.

By the final days, when colour arrived, and the visual practice began to admit warmth, the subject matter had shifted alongside my relationship to it had. The ordinary remained ordinary. The shore was still the shore. But I was looking at it differently: more slowly, more steadily, with less urgency to make it mean something before I had finished seeing it. This is what ver lentamente, seeing slowly, requires more sustained attention to the subjects already present rather than more interesting subjectsined attention to the subjects that are already there. It is, I believe, both the most humble and the most demanding photographic practice I know. And it turns out to be the same practice as healing. You cannot rush either. You can only remain.

References

Ahmed, S. (2012). On being included: Racism and diversity in institutional life. Duke University Press.

Azoulay, A. (2008). The civil contract of photography (R. Mazali & R. Danieli, Trans.). Zone Books.

Berlant, L. (2011). Cruel optimism. Duke University Press.

Boss, P. (1999). Ambiguous loss: Learning to live with unresolved grief. Harvard University Press.

Brown, B. (2010). The gifts of imperfection: Let go of who you think you’re supposed to be and embrace who you are. Hazelden Publishing.

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Doubleday.

Greenspan, M. (2003). Healing through the dark emotions: The wisdom of grief, fear, and despair. Shambhala Publications.

Han, B.-C. (2015). The burnout society (E. Butler, Trans.). Stanford University Press. (Original work published 2010)

Haraway, D. (1988). Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3), 575–599. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066

Hersey, T. (2022). Rest is resistance: A manifesto. Little, Brown Spark.

Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The managed heart: Commercialization of human feeling. University of California Press.

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. (1966, December 16). United Nations Treaty Series, 993, 3. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-economic-social-and-cultural-rights

Kaplan, R., & Kaplan, S. (1989). The experience of nature: A psychological perspective. Cambridge University Press.

Karr, A., & Wood, M. (2011). The practice of contemplative photography: Seeing the world with fresh eyes. Shambhala Publications.

Leavy, P. (2015). Method meets art: Arts-based research practice (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Lorde, A. (1988). A burst of light: And other essays. Firebrand Books.

Nash, R. J. (2004). Liberating scholarly writing: The power of personal narrative. Teachers College Press.

Pink, S. (2013). Doing visual ethnography (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. W. W. Norton.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Slaughter, S., & Rhoades, G. (2004). Academic capitalism and the new economy: Markets, state, and higher education. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Smith, L. T. (2012). Decolonising methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples (2nd ed.). Zed Books.

Sontag, S. (1977). On photography. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Standing, G. (2011). The precariat: The new dangerous class. Bloomsbury Academic.

Tillich, P. (1963). The eternal now. Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Turner, V. (1969). The ritual process: Structure and anti-structure. Aldine.

United Nations. (1948). Universal declaration of human rights. https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights

van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Viking.

Wang, C., & Burris, M. A. (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behaviour, 24(3), 369–387. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019819702400309