Evening

The light is doing that thing again.

Blue dissolving into gold, gold bleeding into rose, rose deepening into violet. Del azul al oro, al rosa y al violeta. I have watched this transformation from this balcony for ten evenings now, and it has never been the same twice. The colour shifts with cloud cover, humidity, and the presence or absence of wind. Each sunset is singular. Unrepeatable. A gift offered once and then gone.

I am learning to receive it without trying to hold it.

This is harder than it sounds. My instinct, trained by decades of academic work, is to document, to analyse, to pin down. To turn experience into data that can be preserved, referenced, and cited. But sunsets resist this treatment entirely. They happen, they transform, they vanish. All you can do is be present while they occur.

Shadows that Haunt Me

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, 2026

Ten days. Diez días.

It feels both longer and shorter than that. Longer because so much has shifted, the sleep that consolidates, the thoughts that clarify, the nervous system that learns to trust. Shorter because time here moves differently from time in my old life. The days unfold rather than accumulate into weeks that must be gotten through. They simply unfold, each one complete in itself.

This morning I wrote about being ready for deeper work.

This afternoon, I discovered whether that was true.

Three hours reading Kaplan and Kaplan’s The Experience of Nature. Dense academic writing. Multiple theoretical frameworks were synthesised. Complex arguments are built across chapters. The kind of scholarship that, a month ago, would have required multiple passes, extensive notes, and constant backtracking to passages still just beyond my grasp.

Today, it made sense on first reading.

Rock Art

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, 2026

Some concepts will need return visits, to sit with, to let marinate. But the basic structure of their argument, the way they build their case for nature experience as psychologically restorative, the relationship they trace between environmental qualities and cognitive restoration: clear. Accessible. My mind is following along without forcing it.

This is what full cognitive capacity feels like. The ability to think deeply, with them. To follow sustained arguments. To hold multiple ideas in relationship. To synthesise.

The relief of this is enormous.

I had begun to wonder whether the cognitive impairment was permanent. Whether months of sleep fragmentation and chronic stress had done lasting damage. Whether I would ever again be able to engage with complex theory the way I once had.

The answer, apparently, is yes. Given sufficient rest, given release from chronic threat, given time for the nervous system to recalibrate, the capacity returns.

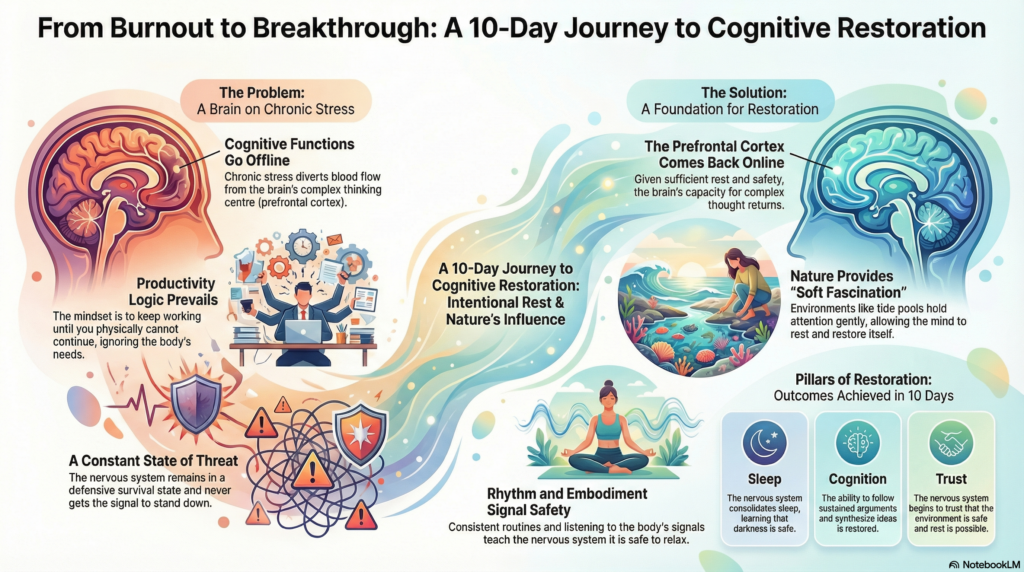

Arnsten’s research on stress and prefrontal function helps me understand why. When the nervous system operates in a defensive state for extended periods, blood flow and glucose are redirected away from the prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain responsible for complex thinking, toward more primitive structures involved in survival. This is adaptive in the short term. Nuanced analysis is useless when facing immediate danger. You need fast, automatic responses.

Google. (n.d.). Google Translate. https://translate.google.com

Google. (2026). From burnout to breakthrough [AI-generated image]. NotebookLM. https://notebooklm.google.com

But when the threat becomes chronic, when the nervous system never gets the signal that it is safe to stand down, those executive functions simply go offline. Offline. Temporarily unavailable. The biological infrastructure that supports complex thought is taken out of commission to conserve resources for survival.

These ten days have convinced my nervous system that the emergency is over. Those resources can be redirected back toward thinking, toward curiosity, toward engagement with ideas.

The prefrontal cortex is online again.

Gracias, cuerpo. Thank you for this restoration.

The Skies Above Me

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, 2026

After reading, I stopped.

This is remarkable, though it may sound otherwise.

For years, I have operated with a productivity logic that says: if you can still function, you should keep working. Rest is what you do when you literally cannot continue. Until then, push.

This afternoon I was tired. Just tired in that natural way, that comes after sustained intellectual engagement. My body said enough for now. And I listened.

I made lunch. Sat on the patio. Ate without reading, without working, without multitasking. Simply ate. Tasted the food. Felt the sun.

Lunch

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, 2026

Then I lay in the hammock for an hour.

Resting, in a hammock in the afternoon with the sound of waves, the movement of air, and the warmth of the sun filtered through palm fronds.

This is what Nash means when he writes about Scholarly Personal Narrative as a practice of presence. Being fully in the experience, beyond just documenting it. Allowing yourself to notice what is actually happening rather than constantly narrating it, analysing it, and turning it into something useful.

Sometimes you just lie in a hammock.

That is the whole story.

Rocks!

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, 2026

Late afternoon, I walked.

Beyond fitness goals or counted steps. Without a destination in mind. Just walking because my body wanted to move, and the beach was there, and the light was beginning to change.

I walked north until I reached the tide pools. Sat on a rock. Watched small crabs scuttle between crevices, tiny fish dart through shallow water, sea anemones open and close their delicate tentacles.

Sea Life

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, 2026

An entire world in a depression carved into stone by centuries of waves.

Time felt different there. Expansive. Unhurried. As though the afternoon had all the space it needed, and there was no rush to get to the evening. Merleau-Ponty (1945/2012) writes about lived time, time as experienced rather than measured. Time expands when you are fully present and contracts when you are anxious about what comes next.

When I finally stood to walk back, my legs were stiff from sitting, but my mind was quiet in a way months had taken from it. The constant low-level hum of anxiety, the voice that is always calculating, planning, worrying about what needs doing next, had simply stopped.

This is what Kaplan calls “soft fascination.” The quality of engagement that holds your attention gently, without effort, without demanding anything. Natural environments provide this. The movement of water. The scuttling of crabs. The opening and closing of anemones. Your attention is engaged and unhurried. And in that gentle engagement, something in the nervous system settles.

Attention Restoration Theory argues that modern life depletes what they call “directed attention,” the capacity to focus on tasks that require effort, to inhibit distraction, and to sustain concentration. We exhaust this capacity constantly: driving in traffic, responding to emails, sitting through meetings, forcing ourselves to concentrate on work that holds little natural interest.

Nature restores directed attention by allowing rest rather than stimulating further. By providing what Kaplan calls “being away,” a break from the demands that deplete us. By offering soft fascination, engagement without effort. By creating compatibility between what the environment offers and what we need in that moment.

Sitting on that rock watching tide pools, I was away. I was softly fascinated. The environment was perfectly suited to what I needed.

And something that had been tightly wound for months finally loosened.

Sea Gulls Fishing

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, 2026

Evening now.

I made dinner as the light began its transformation. Simple food: canned fish with lime, rice, and vegetables. Ate on the patio. Watched the birds complete their final fishing runs before settling for the night.

Dinner Time

The pattern is so familiar now that I could set a clock by it. Morning fishing. The midday rest. The late afternoon fishing. The evening returns to roosting sites. Day after day, the same rhythm.

Rich with variation, Each day holds its own variations. Weather. Wind. The presence or absence of baitfish near the surface. Sometimes the pelicans fish alone. Sometimes in groups. Sometimes they dive from great heights. Sometimes they simply skim the surface, plucking small fish without submerging.

The rhythm allows for variation. The variation occurs within rhythm. Neither negates the other.

I am learning this. Estoy aprendiendo esto.

Slowly.

What has ten days built?

I have been asking myself this as the light fades and the first stars appear. What is different now from ten days ago when I arrived at this cottage, suitcase still packed, uncertain whether I knew how to stay?

Sleep: Three nights of sleeping through. The pattern is consolidating. My nervous system, learning that night, means rest: that darkness is safe, that vigilance can be released for seven hours without catastrophe.

Cognition: Prefrontal cortex restored. Can read complex theory. Follow sustained arguments. Synthesise across frameworks. Think without forcing each thought into existence through sheer will.

Embodiment: Being in my body rather than trying to manage it from outside. Can feel sensations without them being threatening. Can notice needs before they escalate into emergencies.

Rhythm: Evening sequence established. Morning patterns are consolidating. The body learning to read time through environmental cues, light quality, temperature, the pelicans’ flight patterns, rather than the external demands that structured my old life.

Trust: the foundation beneath everything else. My nervous system is beginning to trust. Trust that this environment is safe. Trust that rest will come. Trust that the next crisis can find me unhurried, the next email that changes everything, the next announcement that requires scrambling, repositioning, and proof of worth.

The foundation holds.

Tomorrow I will build on it. More reading. More theoretical engagement. Days eleven through twenty moving toward integration, bringing embodied experience into conversation with scholarly frameworks. Seeing how research illuminates what the body already knows. Contributing, eventually, to conversations about solitude and healing and the conditions that support nervous system regulation.

But tonight I simply rest in what ten days have created. In the capacity that has been restored. In the trust built brick by brick, through consistent rhythms and environmental cues, my conscious mind barely registered, but my nervous system tracked with precision.

Sea of Cortez

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, 2026

Long enough to begin.

In an hour, I will begin the evening sequence. The rituals my nervous system has learned to recognise as the approach of rest.

Dinner already eaten. Dishes washed. Cottage tidy. All the small acts of care that signal: evening is here, night is coming, you can begin to let go.

Will I sleep through tonight? Fourth night in a row would confirm the pattern even more strongly. It would give my system even more evidence that this is real, sustainable, and trustworthy.

But even if I wake, even if tonight fragments again, I know more now than I did ten days ago. I know what supports sleep. I know what environmental cues signal safety. I know how to maintain conditions even when the immediate results fall short of my hopes.

Healing releases control of outcomes. It is about maintaining conditions and trusting the system to respond.

I cannot force my nervous system to trust. But I can keep creating the circumstances that make trust possible. Keep following rhythms. Keep honouring the body’s signals. Keep providing the environmental conditions required for safety.

The actual sleeping, the actual healing, the actual transformation. These happen in their own time. Beyond conscious control. According to processes more ancient and wiser than anything my conscious mind can manage.

All I can do is maintain the conditions and step aside.

El umbral. The threshold.

I stand on it tonight. Looking back at the ten days that built a foundation. Looking forward to twenty more that will build on it.

Here. On this threshold. Leaving what was behind, arriving toward what comes next. Noticing what is.

The foundation holds. My body knows this. My nervous system has learned it through accumulated evidence that conscious thought played almost no role in gathering. Tomorrow I build upward from here.

But tonight, esta noche, I rest.

The pelicans have settled for the evening, wherever it is they go when light fails, and the sea turns dark. The stars are beginning to appear, one by one, then a handful, then too many to count. The waves continue their patient rhythm, the same rhythm they have maintained for millions of years, the same rhythm they will maintain long after I have left this place and returned to whatever life awaits me back home.

And I sit on the balcony on the tenth evening, holding the question that all thresholds hold:

What becomes possible when the foundation is sound?

Tomorrow I begin finding out.

La fundación sostiene.

The foundation holds.

Mañana construimos hacia arriba.

Tomorrow we build upward.

Pero esta noche, solo esto.

But tonight, just this.

El mar. Las estrellas. El ritmo constante.

The sea. The stars. The constant rhythm.

Y un cuerpo que finalmente descansa.

And a body that finally rests.

From Burnout to Breakthrough

Credit: NotebookLM, 2026

Translation Note

Note. Spanish-language passages were generated using Google Translate (Google, n.d.) and subsequently reviewed and refined by the author. Any remaining infelicities reflect the limits of machine translation rather than intent.

References

Arnsten, A. F. T. (2009). Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(6), 410–422. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2648

Kaplan, R., & Kaplan, S. (1989). The experience of nature: A psychological perspective. Cambridge University Press.

Kaplan, S. (1995). The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15(3), 169–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-4944(95)90001-2

Merleau-Ponty, M. (2012). Phenomenology of perception (D. A. Landes, Trans.). Routledge. (Original work published 1945)

Nash, R. J. (2004). Liberating scholarly writing: The power of personal narrative. Teachers College Press.