What Makes Restoration Possible

When the Sky Speaks

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, 2026

The sky is doing that thing again. Blue becomes gold, becomes rose, becomes violet, and if you blink, you miss the exact moment one colour surrenders to the next. Del azul al oro, al rosa y al violeta. (For the record, I have to look up every word in Spanish in my translator.) I have been sitting here on the balcony watching it happen, trying to find words for what today felt like, and I keep circling back to the same inadequate word: different.

Different. And yes, better.

Coffee by the Sea

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, 2026

Different in a way that makes me realise how long I have been living in that other place. The one where everything costs. Where even simple things, getting out of bed, making coffee, being present in my own life, require negotiation and force and that particular grinding willpower that is really just exhausted determination wearing a productivity costume.

Today arrived without force. No tuve que forzar nada.

I woke without the usual calculation of whether I had enough in the tank to make it through. No caffeine required, no stubbornness invoked to override my body. No careful rationing of attention, like it might run out before sunset.

Things just… happened. Todo fluyó. Thoughts connected. Words came. My body moved through space without requiring constant management. Natural. Like breathing. Like the way I imagine other people, rested people, move through their days without even noticing how easy it is.

Three hours

This morning I wrote for three hours. Tres horas. The kind of writing where you look up and realise time passed, and you were simply in it, beyond the counting, beyond the forcing of each sentence into existence through sheer will.

I wrote about what happened last night. About sleep architecture and nervous system states, and why my body finally trusted enough to sleep through. I wove together material from Walker (2017) on sleep cycles and Porges (2011) on the polyvagal system, along with what actually happened in my own body between 11 PM and 6 AM. Complex theoretical frameworks are talking to each other through my experience. All of it makes sense. All of it flowing.

Sleep Cycle

Created: Gemini AI, 2o26

Three months ago, this would have been impossible.

Beyond hard. Impossible.

And I need to be precise about that distinction because it matters.

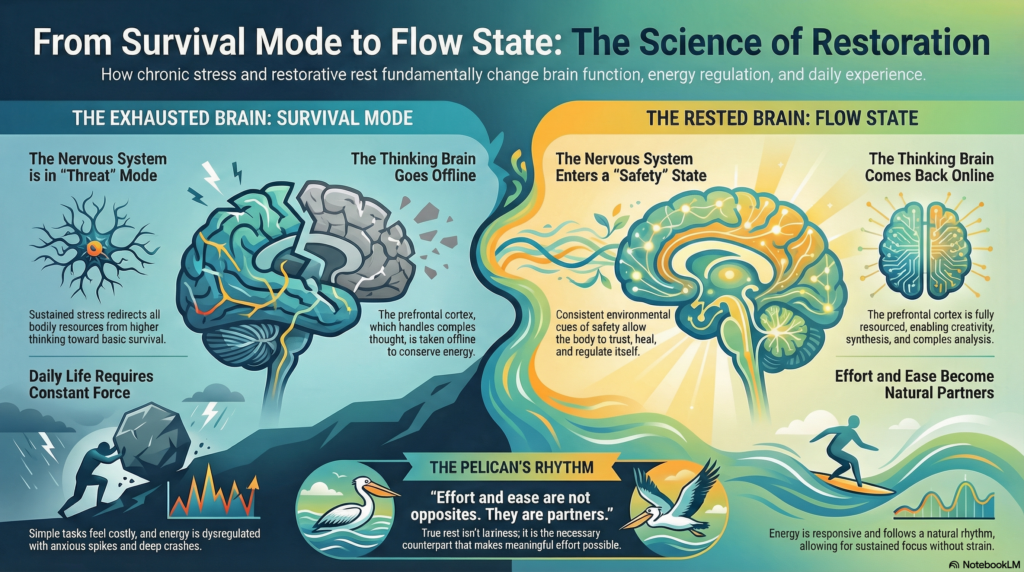

There is this thing that happens when you have been stressed and sleep-deprived for long enough. People talk about it like you are just a little foggy, a little slower, like turning down the volume on a radio. That description misses what it feels like from inside. From inside, it feels like parts of your brain just… stop. Go dark. Offline (Arnsten, 2009).

The prefrontal cortex, the part that does complex thinking, that holds multiple ideas at once, that synthesises and integrates and makes connections, needs massive resources to run. Blood flow. Glucose. Energy. And when your body thinks it is in danger, when your nervous system has been reading the environment as threatening for weeks or months, those resources get redirected. Away from thinking, toward surviving. The amygdala scans for threats. The brainstem is ready to react. Ancient survival systems running the show while the thinking parts go quiet (Arnsten, 2009; Goldstein & Walker, 2014).

Which makes perfect evolutionary sense if you are running from a predator. Nuance is useless when you need to run. You need fast, automatic, proven responses.

The problem is that economic precarity (precariedad económica) is no predator. Contract uncertainty cannot be outrun. But try telling that to a nervous system running million-year-old software that says: sustained threat equals redirect all resources to survival.

So the thinking parts go offline. Executive functions dim. And you tell yourself you are just tired, that you need to try harder, that you need more coffee.

Untitled

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, 2026

Except that trying harder proves ineffective when the biological structures that underpin complex thinking have been taken offline to conserve resources for mere survival.

This morning, those structures were back. I could feel it, bodily, somáticamente, in my actual body. I read something from Walker’s work, and I could hold the concept while simultaneously connecting it to Porges and to what happened in my own sleep last night. Three frameworks, held together, talking to each other in my mind.

A month ago, reading that same passage, I would have had to stop. Reread. Make notes. Force comprehension through sheer determination. Today it just… made sense. La comprensión fluyó. Understanding flowed.

The Dissertation

After lunch, I did something I have been avoiding. I opened my dissertation files. The pages I wrote months ago when sleep was breaking every night, when my nervous system was in constant alert, when exhaustion had become so normal I had stopped recognising it as a state separate from just being me. Yes, in addition to pursuing a Master’s in Human Rights and Social Justice, I am also completing a doctorate.

I was bracing for it to be bad. Full of gaps. Incoherent in places. The kind of work you produce when your prefrontal cortex is running on fumes, and you are just trying to get through.

It was good. Actually, genuinely good. The arguments held. The theory was solid. The thinking was clear.

And I sat there staring at these pages I wrote while barely functional and felt this complicated tangle of relief and grief. Una especie de duelo. Because if I could do that work while exhausted, produce something sound while my body was in survival mode, while parts of my brain were literally offline, what might I have been capable of if I had been rested?

What did I lose to those months of pushing through?

I watched the pelican outside my window for a long time. Dive. Rest. Zambullirse y descansar. Dive. Rest. Over and over. That simple rhythm. And something shifted in how I was thinking about the question.

The assumption underneath my grief was that exhausted-me and rested-me are the same person in different states. But that framing misses something. The work I produced while exhausted was shaped by that exhaustion. The questions I asked, the frameworks I reached for, the way I approached the material: all of it came from living inside chronic activation and precarity.

That work has value because it was written from within the very thing it seeks to understand. Nash (2004) argues that lived experience (experiencia vivida) is legitimate scholarly data when you examine it rigorously. My exhaustion was enriching the work. It was part of the data.

What restoration gives me goes beyond redoing that work “properly.” It is the chance to add another layer. To examine chronic activation from the perspective of someone who has lived both states and can now see the relationship between them.

Both matter. Both are real. Both contribute.

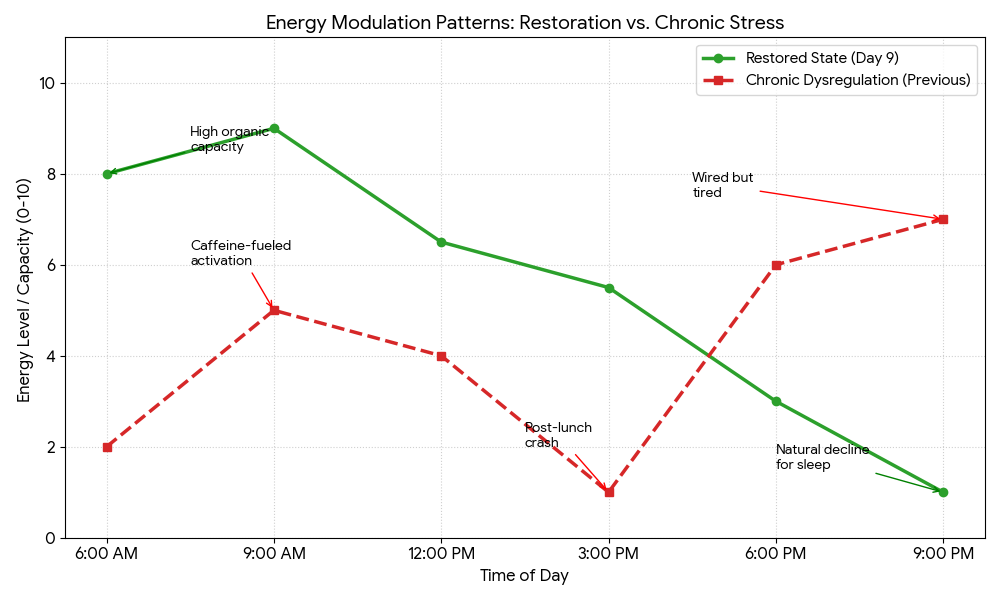

I have been writing down what I notice in my body at different points today. For no formal reason. Just because the consistency seemed worth documenting.

Morning: Waking without an alarm. The body knows what time it is from some internal clock that fragmented sleep had disrupted. That feeling of being actually rested sinks all the way into my bones. Quiet joy mixing with disbelief, mixing with gratitude. High energy but organic, unforced, free of chemical aid, just available. First conscious thought: I slept through.

Mid-morning: Three hours of writing behind me. Shoulders loose. Jaw soft. Hands steady. That focused clarity without the edge of strain I am so used to. Still high energy, sustained without effort. No fatigue. Apparently, complex intellectual work thrives beyond defensive nervous system states. Who knew.

Afternoon: After lunch. Gentle hunger satisfied. Digestion easy. Muscles relaxed. Just… contentment. Being in my body instead of trying to manage it from somewhere outside. Energy is moderate now, appropriate to midday. Body speaking up clearly about needs: thirst, hunger, time to move, instead of waiting until an emergency before getting my attention.

Later afternoon: Reading dissertation. Sitting comfortably without conscious effort. No tension accumulating in neck and shoulders. Emotions complex, that relief-grief tangle, present but manageable. Holding contradictory feelings without my nervous system reading emotional complexity as a threat. Energy is holding steady.

Evening: Sunset. Cooling air. Breath synchronised with waves. Body at ease. Deep peace. That gentle anticipation of evening unfolding. Energy naturally declines as the day winds down. Unwound rather than crashed. Present rather than depleted. Responsive to circadian rhythms, to what is actually needed now.

Night: Preparing for sleep. The body is already beginning the transition. Muscles releasing. Calm. Trust that sleep will come, that my body knows how to do this. Very low energy, sleep-ready. And here is what strikes me: no anxiety about whether tonight will repeat last night. Just readiness.

Looking at this pattern, the way energy moved across the day, I can see how it is supposed to work. La naturalidad. The naturalness of it. High when needed for writing. Moderate for reading. Naturally declining toward rest. Responsive. Appropriate. Organic.

For months, my energy looked nothing like this. Low despite caffeine. Forced into function through will. Brief spikes when adrenaline kicked in. Complete crashes. Forced back up. Anxious and activated at night when I needed sleep.

That is dysregulation wearing a performance of function. That is dysregulation. That is what happens when the nervous system cannot access the state that allows for appropriate energy modulation.

Today, my energy followed the pattern research says is healthy (Kaplan, 1995; Ryan & Deci, 2000). And I know that sounds abstract, mere “research says” abstraction, but from inside it feels like my body finally remembering how to be a body. How to respond to actual needs instead of just surviving threat after threat after threat.

The Pelican’s Teaching

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, 2026

My hands wanted charcoal this afternoon. For no reason except they wanted it. So I drew the pelican. El pelícano. The one I have been watching all week. Beyond accuracy, Trying to capture the quality of movement. The dive. The pause. The rest. El ritmo. That rhythm.

And here is what I am seeing: effort and ease work as partners. El esfuerzo y la facilidad no son opuestos. They are partners.

The dive takes everything. Wings folding, body plummeting, that violent entry into water, struggling with a fish. Real effort. Then the rest is complete. Body still on the surface, conserving, digesting. Real rest.

Neither negates the other. The effort is recognised; it simply requires rest. The rest is earned, because it follows effort. They are both necessary. Both are part of the natural rhythm.

I have been living like they are in competition. Like rest is something I have to earn through sufficient effort. Like, I can only access it once I have accomplished enough to justify it. Like needing rest means I am weak or inefficient or somehow failing.

El pelícano no piensa así. The pelican holds no such story. The pelican dives when hungry. Rests because the body needs to conserve energy between dives. Neither requires justification. Both are what the body needs.

I am learning this. Despacio. Slowly. Con dificultad. With difficulty. But learning.

What I am afraid of

It is almost time for bed, and there is a question I have been avoiding all day. What if last night was a fluke? What if tonight I wake at 2 AM with thoughts racing? What if my nervous system’s trust was temporary, contingent, fragile?

I can feel anxiety activating around this. Shoulders tensing. Breathe shallow. Hypervigilance creeping back: scanning, trying to control, attempting to guarantee through worry that last night repeats.

But here is what I learned this morning, what the research showed me: nervous systems bypass conscious decisions about safety entirely. They respond to environmental cues. Señales ambientales. To patterns repeated across time. To accumulate data (Porges, 2011).

Nine nights now. Same evening sequence. Same environmental cues. That is data my nervous system has been gathering.

One night of unbroken sleep does something more interesting than erase that pattern. It confirms it. The conditions that supported last night’s rest remain. Evening rhythm is stable. The acoustic environment provides low-frequency, rhythmic patterns that signal safety. Darkness is complete and held safely. Predictability that allowed my system to trust enough to release vigilance.

I cannot control whether I sleep through tonight. But I can maintain the conditions that supported last night. Follow the same sequence. Honrar el ritmo. Honour the rhythm. Trust my nervous system is doing what nervous systems do: gathering data, testing predictions, updating assessments.

And if I wake tonight? That is also data. Data. Information about how healing actually proceeds when you get close enough to see it.

Nine days

Nueve días. Nine cycles of morning and evening. Nine progressions dark to light to dark. The pattern repeats but is never exactly the same. Each day is similar in structure, unique in texture, in quality, in what it shows me.

Today showed capacity. Hoy reveló capacidad. The capacity to think clearly. Write with rigour and creativity. Hold complexity without overwhelm. Feel contradictory emotions without dysregulation. Notice what the body needs and respond appropriately.

I had begun to think these capacities were gone. Diminished permanently by months of stress and fragmentation. But they were offline, waiting. Estaban desconectadas. Waiting for conditions that would let them function.

Last night’s unbroken sleep provided those conditions. Seven hours of sustained regulation. Seven hours of complete sleep cycles. Seven hours of trust.

And today, the harvest. La cosecha de ese descanso. Clear thinking. Sustained energy. Natural rhythms.

Tomorrow night will bring its own data. Sleep through or wake, either contributes to understanding. The nervous system is learning what safety feels like. El sistema nervioso está aprendiendo cómo se siente la seguridad. Learning to recognise it. Trust it. That learning moves in spirals, circling back. Some nights, complete rest, some partial waking. Both teaching the system about regulation, about what supports healing, about the gradual recalibration from threat to safety.

What Direction?

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, 2026

What I know tonight, sitting here as the last light fades and first stars appear above the sea, mientras se desvanece la última luz del cielo y aparecen las primeras estrellas sobre el mar: healing is something concrete and measurable, It is a concrete, lived, measurable reality.

My body slept through last night. First time in months.

My mind engaged in complex theoretical work today. First time in weeks.

My energy modulated appropriately across the day. First time I can remember.

Facts. Data points. The larger pattern of regulation and recovery is becoming visible.

El ritmo continúa. The rhythm continues. The pattern repeats. The body learns. And I, finally, am learning to trust this.

Figure 2: From Survival Mode to Flow State

Credit: NotebookLM, 2026

Gracias, cuerpo. Thank you, body.

Por este día de claridad. For this day of clarity.

Por mostrarme lo que es posible cuando descansas. For showing me what is possible when you rest.

Por enseñarme que el esfuerzo y la facilidad son socios, no enemigos. For teaching me that effort and ease are partners.

Por el ritmo. For the rhythm.

The Lion’s Breath

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, 2026

Translation Note

Note. Spanish-language passages were generated using Google Translate (Google, n.d.) and subsequently reviewed and refined by the author. Any remaining infelicities reflect the limits of machine translation rather than intent.

References

Arnsten, A. F. T. (2009). Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(6), 410–422. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2648

Goldstein, A. N., & Walker, M. P. (2014). The role of sleep in emotional brain function. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 10, 679–708. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153716

Google. (n.d.). Google Translate. https://translate.google.com

Google. (2026). From survival mode to flow state [AI-generated image]. NotebookLM. https://notebooklm.google.com

Kaplan, S. (1995). The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15(3), 169–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-4944(95)90001-2

Kaplan, R., & Kaplan, S. (1989). The experience of nature: A psychological perspective. Cambridge University Press.

Nash, R. J. (2004). Liberating scholarly writing: The power of personal narrative. Teachers College Press.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. W. W. Norton & Company.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Walker, M. (2017). Why we sleep: Unlocking the power of sleep and dreams. Scribner.

What restoration makes possible — the return of curiosity, appetite, creative impulse — is the clinical literature's definition of recovery from burnout (Maslach, Schaufeli, & Leiter, 2001): the restoration of engagement, efficacy, and energy that chronic overextension depletes. Ryan and Deci's (2000) self-determination theory frames this as the re-emergence of intrinsic motivation once external demands are suspended. This entry marks a pivot point in the inquiry: the beginning of the third phase, where alonetude stops being survival and starts being inquiry.