When the Body Finally Rests

Understanding Sleep Architecture and What It Requires for Healing

Desert Rose

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, 2026

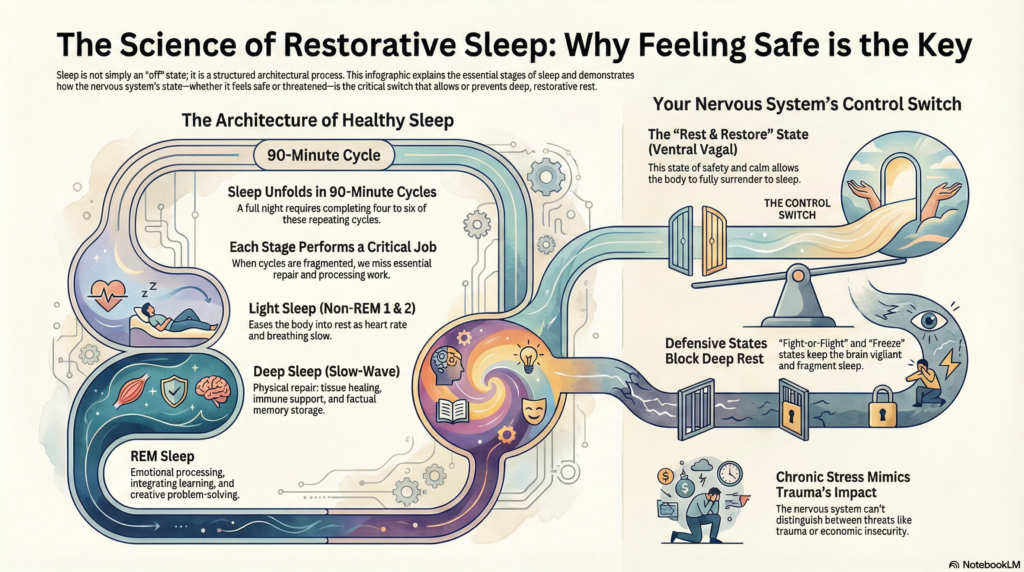

To understand why last night matters so much, why one night of unbroken sleep marks such an important moment in this healing process, I need to explain how sleep actually works. I came to grasp this fully only after reading the research. Sleep is layered, active work. It is far more than “being unconscious” for seven or eight hours. Sleep is a process, a carefully organised progression through distinct stages that unfolds in a specific order throughout the night. Researchers refer to this pattern as sleep architecture (Walker, 2017).

Here is how it works. When we sleep, we move through stages. There are stages of light sleep, which researchers call Stage 1 and Stage 2 non-rapid eye movement sleep, or non-REM sleep for short. Then there is deep sleep, the third stage of non-REM sleep. Scientists also call this slow-wave sleep because, when they measure brain activity during this stage with an electroencephalogram, they see large, slow waves. Finally, there is rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, named for the rapid eye movements that occur during this stage, even though the body is asleep (Walker, 2017).

We cycle through all stages all night. Instead, we repeatedly cycle through all of these stages. One complete cycle, from light sleep through deep sleep to REM sleep and back, takes about ninety minutes. A good night’s sleep involves completing four to six of these cycles, which is why we need seven to nine hours of sleep (Walker, 2017).

What I am learning is that each stage does something different and important for the body and mind. Light sleep is a transitional state. It eases us from being awake into deeper states. During this stage, our heart rate slows, our breathing steadies, and we begin to disconnect from what is happening around us. Deep slow-wave sleep is when the body undergoes physical repair. This is when tissues heal, the immune system strengthens, growth hormones are released, and our brains store the factual information we learned during the day, the kind of memory we can consciously recall later (Walker, 2017). REM sleep does different work. This is when we process emotions, when our brains integrate new learning with what we already know, when creative problem-solving happens, and when our psychological equilibrium gets maintained (Germain, 2013; Walker, 2017).

When sleep gets fragmented, when we wake up frequently or leave cycles incomplete, we miss essential processes. The body is unable to finish its maintenance work. This is what had been happening to me for months.

What the research taught me, and what my own body confirmed over these nine days, is that this architecture requires a specific function of the nervous system. Progression through these stages occurs only when the nervous system is in a particular state. Stephen Porges (2011, 2022), who developed something called Polyvagal Theory, calls this the ventral vagal state. I will explain what this means because it is central to understanding what changed last night.

The ventral vagal complex is part of the parasympathetic nervous system, which is associated with rest and restoration. Porges describes it as the most recent evolutionary branch of this system, unique to mammals. When we are in this ventral vagal state, we feel safe. Our bodies can engage socially with others. Porges calls this “mammalian calm,” the state that allows for rest, restoration, intimacy, and even play. You can recognise this state in the body: the heart rate steadies with healthy variability, breathing is calm, the facial muscles relax, and we can make comfortable eye contact with others. And critically for sleep, in this state, we can surrender to unconsciousness without our nervous system remaining vigilant, constantly scanning for threats (Porges, 2011, 2022).

Crown of Thorns

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, 2026

The problem is that when the nervous system remains in a defensive state, sleep deteriorates. There are two main defensive states. One is sympathetic activation, commonly known as the fight-or-flight response. When this system activates, heart rate increases, cortisol rises, muscles tense, and alertness heightens. The body is preparing to fight or run. The other defensive state is dorsal vagal shutdown, also known as the freeze or collapse response. This is when the body immobilises, when we dissociate, when we metaphorically “play dead” because the threat feels overwhelming (Porges, 2011, 2022). When the nervous system stays in either of these defensive states, sleep becomes fragmented, shallow, and non-restorative (Germain, 2013; Mellman et al., 2002). The hypervigilance, the constant scanning for potential threats, prevents the deep relaxation that complete sleep cycles require. The nervous system resists fully surrendering to sleep because, below conscious awareness, it assesses that doing so would leave us vulnerable to harm.

The research on trauma makes this relationship very clear. People diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, show severely disrupted sleep across multiple measures. Their sleep architecture looks broken. They obtain significantly less slow-wave sleep, resulting in less physical restoration. Their REM sleep is highly fragmented, compromising emotional processing. They wake frequently during the night, driven by what researchers call autonomic hyperarousal, the nervous system’s persistent scanning for threat operating even during sleep (Germain, 2013; Mellman et al., 2002; van der Kolk, 2014).

But here is what matters for understanding my own experience: diagnosable PTSD is unnecessary to experience these patterns. Chronic occupational stress, particularly the sustained and unpredictable stress of precarious employment, produces remarkably similar patterns through the same underlying mechanism (Åkerstedt, 2006; Lallukka et al., 2010). Economic precarity, the sustained threat to livelihood and financial security, generates the same kind of autonomic hyperarousal that traumatic events produce. The nervous system cannot distinguish between different types of threats to survival. It responds to the pattern of threat rather than to the specific content.

When I say I slept through the night, I mean that my autonomic nervous system maintained a ventral vagal state, that state of felt safety, across multiple ninety-minute sleep cycles for seven consecutive hours. My body held the physiological state associated with safety long enough to complete the full restorative architecture of sleep. This is something my system has been unable to accomplish for longer than I want to admit.

Desert Rose

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, 2026

Nine days. Nine complete cycles of consistent environmental cues, predictable daily rhythms, and the systematic absence of things my nervous system reads as threats. That is what it took for my nervous system to shift its baseline assessment from “unsafe, must remain vigilant” to “safe enough to rest completely.”

Table 1

Sleep Architecture and Autonomic States: Physiological Functions, Indicators, and Impacts of Disruption

| Sleep Stage or Physiological State | Category | Description and Biological Function | Physical Indicators | Impact of Disruption or Stress | Key Research Citations | Source |

| Stage 1 & 2 Non-REM | Non-REM Sleep (Light Sleep) | Transitional states that ease the body from wakefulness into deeper sleep and progressive disconnection from the environment, supporting essential maintenance processes and preparation for restorative sleep. | Slowing heart rate; steadier breathing; reduced muscle tone. | Fragmentation disrupts maintenance processes and prevents progression into deeper restorative sleep cycles. | Walker (2017) | The Architecture of Sleep and the Science of Safety |

| Stage 3 Slow-wave Sleep | Non-REM Sleep (Deep Sleep) | Primary stage for physical repair, tissue healing, immune strengthening, and growth hormone release; supports consolidation of factual and recallable memories. | Large, slow brain waves measured by EEG (delta waves). | Loss of physical restoration; markedly reduced in individuals experiencing chronic stress or PTSD. | Walker (2017); Germain (2013); Mellman et al. (2002); van der Kolk (2014) | The Architecture of Sleep and the Science of Safety |

| REM Sleep | Rapid Eye Movement Sleep | Processes emotions, integrates new learning with prior knowledge, supports creativity, and maintains psychological balance. | Rapid eye movements with muscle atonia; variable heart rate and breathing. | Fragmentation impairs emotional processing and memory integration; commonly interrupted by autonomic hyperarousal in PTSD. | Walker (2017); Germain (2013); Mellman et al. (2002) | The Architecture of Sleep and the Science of Safety |

| Ventral Vagal State | Parasympathetic State (Rest and Restoration) | State of felt safety that enables rest, social engagement, and the capacity to surrender to unconsciousness without vigilance. | Steady heart rate with healthy variability; calm breathing; relaxed facial muscles; ease in eye contact. | Inability to sustain this state interrupts restorative sleep cycles and shifts the system into defensive states. | Porges (2011, 2022) | The Architecture of Sleep and the Science of Safety |

| Sympathetic Activation | Defensive State (Fight-or-Flight) | Mobilization response to perceived threat, maintaining alertness and readiness for action. | Elevated heart rate; increased cortisol; muscle tension; heightened alertness. | Sleep becomes shallow, fragmented, and non-restorative as the body resists relinquishing vigilance. | Porges (2011, 2022); Germain (2013); Mellman et al. (2002) | The Architecture of Sleep and the Science of Safety |

| Dorsal Vagal Shutdown | Defensive State (Freeze or Collapse) | Immobilization response to overwhelming threat, associated with dissociation and withdrawal. | Reduced movement; dissociation; lowered metabolic activity. | Produces fragmented, non-restorative sleep and prevents the deep relaxation required for full sleep architecture. | Porges (2011, 2022); Germain (2013); Mellman et al. (2002) | The Architecture of Sleep and the Science of Safety |

Note: This table integrates sleep-stage physiology with autonomic nervous system states to illustrate how safety, threat, and stress shape sleep quality. It emphasises the interdependence between sleep architecture and autonomic regulation in restorative sleep and in trauma-related disruption.

The Science of Resorative Sleep

Created by Notebook LM, 2026

This moment has clarified that restorative sleep is neither accidental nor simply a matter of time spent in bed. It is an embodied outcome of safety. Sleep architecture unfolds fully when the nervous system assesses the environment and the broader conditions of life as safe enough to release vigilance. One uninterrupted night mattered because it marked a physiological shift rather than a behavioural one. My body sustained a ventral vagal state long enough to complete multiple cycles of repair, integration, and emotional processing. Healing, in this sense, emerged through conditions rather than effort. It arose as the threat receded, rhythms stabilised, and my nervous system received permission to rest. This understanding reframes sleep as a diagnostic signal of safety and a quiet indicator of recovery already underway.

References

Åkerstedt, T. (2006). Psychosocial stress and impaired sleep. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 32(6), 493–501. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.1054

Germain, A. (2013). Sleep disturbances as the hallmark of PTSD: Where are we now? American Journal of Psychiatry, 170(4), 372–382. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12040432

Lallukka, T., Rahkonen, O., Lahelma, E., & Arber, S. (2010). Sleep complaints in middle-aged women and men: The contribution of working conditions and work-family conflicts. Journal of Sleep Research, 19(3), 466–477. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2869.2010.00821.x

Mellman, T. A., Bustamante, V., Fins, A. I., Pigeon, W. R., & Nolan, B. (2002). REM sleep and the early development of posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(10), 1696–1701. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1696

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. W. W. Norton & Company.

Porges, S. W. (2022). Polyvagal theory: A science of safety. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 16, Article 871227. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnint.2022.871227

van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Viking.

Walker, M. (2017). Why we sleep: Unlocking the power of sleep and dreams. Scribner.

Google. (2026). Sleep cycle [AI-generated image]. Gemini. https://gemini.google.com

Google. (2026). The science of restorative sleep [AI-generated image]. NotebookLM. https://notebooklm.google.com

Finding a morning rhythm in a new place is a form of what Csikszentmihalyi (1990) calls the early conditions for flow: a structure that is self-chosen, repeatable, and calibrated to one's own pace. The body's uptake of a different daily rhythm also reflects Porges's (2011) polyvagal model: the nervous system co-regulating with the environment rather than with institutional time. Rhythm, here, is not productivity — it is the somatic baseline from which genuine inquiry becomes possible.