What If I Let Go

I woke this morning with a tightness in my chest that had nothing to do with the night before.

The sleep had been deep, the room cool, the sea audible through the open window. Everything about this place says rest. And yet my body woke braced, as though preparing for something that never arrived.

I lay still for a long time, watching the ceiling lighten. Trying to name what I was feeling.

It took a while to find the word. When it came, it surprised me.

Fear.

The Shape of It

The fear lives elsewhere. I have settled into Loreto more easily than I expected. Solitude has become companionable. Silence I am learning to inhabit.

The fear is of what happens if I truly let go.

For years, decades, I have held myself together through effort. Through vigilance. Through the constant, quiet work of monitoring, anticipating, and performing competence. I have been the one who could be counted on. The one who showed up prepared. The one who held more than her share because holding felt safer than asking for help.

That holding has become so familiar that I cannot quite imagine who I would be without it.

And so the fear: if I release the grip, if I stop the vigilance, if I truly rest, will I ever want to return to life as it was? Will I lose the capacity for striving that kept me employed, that kept me useful, that kept me worthy of belonging?

Will I, in some fundamental way, stop being the person I have always been?

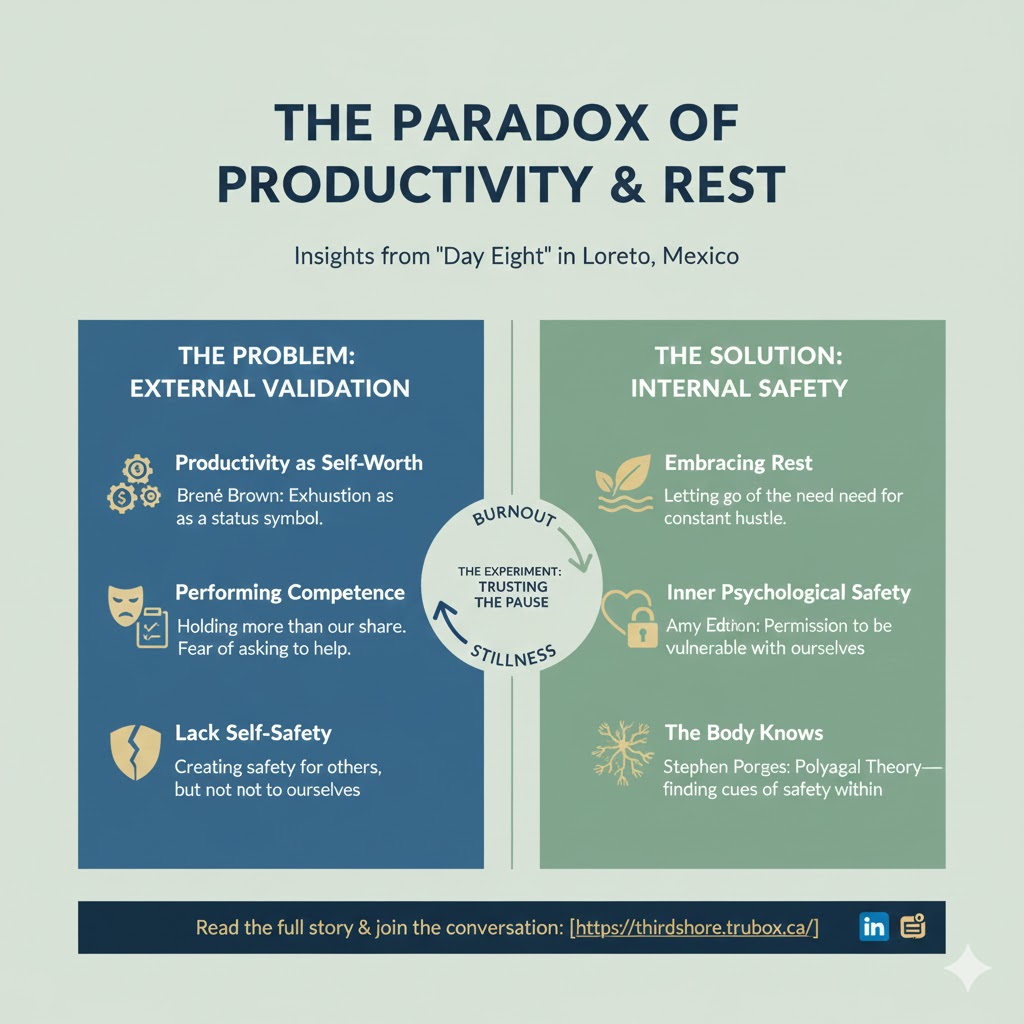

The Paradox: Productivity and Rest

Created by Gemini AI Tool, 2026

The Paradox of Letting Go

There is a strange paradox here. I came to this retreat because I was exhausted by the holding. Because the vigilance had worn grooves in my nervous system that no longer served me. Because I wanted, desperately, to rest.

And now that rest is possible, I am afraid of it.

Afraid that rest will undo me. That I will sink into it and never surface. The woman who emerges from this month will be unrecognizable to herself and to others. That she will have lost her edge, her drive, her usefulness.

The fear reveals how deeply I have tied my worth to my capacity for effort. How thoroughly I have believed that I am only as valuable as what I produce.

Brené Brown (2010) calls this the use of exhaustion as a status symbol and productivity as self-worth. She identifies it as one of the things we must consciously release if we want to live what she calls a wholehearted life. Reading those words years ago, I nodded in recognition. Living them is harder.

Halfway There

Credit: Amy Tucker, 2026

Creating Safety for the Self

In my academic work, I have written about psychological safety: the conditions that allow people to take interpersonal risks without fear of embarrassment, shame, or punishment (Edmondson, 1999). In classrooms and workplaces, psychological safety means being able to ask questions, admit mistakes, and offer ideas that might fail. It means knowing that vulnerability will be met with support rather than judgment.

I have spent years trying to create psychological safety for students. I have rarely thought about creating it for myself.

What would it mean to approach my own interior with the same care I offer others? To make it safe for myself to rest without proving I deserve it? To let go without requiring a plan for what comes next?

Psychological safety, I am learning, begins within. It begins with the quiet assurance that I will stay with myself, whatever surfaces. That I will meet my need for rest with gentleness. That I will carry this retreat forward as what it is: a return to myself.

The body knows when it is safe. Stephen Porges (2022) has shown that feelings of safety arise from internal physiological states and from cues that signal the nervous system can stand down from vigilance. Those cues can come from the environment, from the relationship, from the breath, from the stillness.

They can also come from the stories we tell ourselves about what we are allowed to need.

The Fear Beneath the Fear

There is another fear beneath this one, harder to name.

I am afraid that if I let go completely, I will lose the capacity to love the life I have built. That the stillness will reveal how much of my striving was compensation rather than calling. That I will look back at my career, my choices, my years of effortful contribution, and feel only exhaustion rather than meaning.

I am afraid of becoming someone who no longer wants to return.

And beneath even that: I am afraid that letting go will reveal an emptiness I have been running from. That, without the structure of obligation, without the identity of educator, without the constant motion, I will find nothing but blank space where a self should be.

This is the fear that woke me this morning. This is what tightened my chest before dawn.

Staying With It

I left my phone untouched. I resisted the pull toward plans or tasks or the small urgencies that usually rescue me from discomfort.

I stayed.

I let the fear be present without trying to fix it. I breathed into the tightness in my chest. I asked, with as much curiosity as I could muster: What are you trying to protect?

The answer came slowly. The fear is trying to protect me from loss. Loss of identity. Loss of purpose. Loss of the scaffolding that has held my life in place for so long.

I thanked it. I mean that genuinely. The fear has kept me functional through years that might otherwise have broken me. It has helped me show up when showing up was required. It has been a kind of armour, and armour serves a purpose.

But armour is heavy. And I am in a place now where I can set it down, even briefly. Even experimentally.

An Experiment in Trust

What if letting go means finding? What if the woman who emerges from stillness is clarified rather than diminished? What if rest reveals presence rather than emptiness?

I cannot know without trying. I cannot know from the outside. I can only know by going in.

Brown (2010) writes about cultivating intuition and trusting faith, which requires letting go of the need for certainty. Certainty is what I have always sought. Plans, structures, contingencies. The illusion that if I prepare enough, I can prevent loss. The illusion that control keeps me safe.

Here in Loreto, the illusion is harder to maintain. The sea holds itself apart from my plans. The mountains hold their shape with or without my watching. The pelicans fish without consulting my schedule. Life here unfolds without my management, and it unfolds beautifully.

Perhaps I, too, can unfold without so much management.

Perhaps the self that emerges from stillness will be someone I recognise after all. Perhaps she will be someone I have been waiting to meet.

Morning, After

I made coffee. I carried it to the small balcony. I sat in the chair that had become familiar over these eight days and watched the light strengthen over the water.

The fear remained. It sat beside me like a companion, still present but no longer gripping. I had acknowledged it. I had listened. I had refused to let it drive me back into motion.

This, I think, is what the discipline of staying means. It means feeling the fear fully. It means feeling the fear and remaining anyway. It means creating enough safety within myself to be present with uncertainty, with open-handedness, with the vulnerability of letting go.

The morning was quiet. A boat moved slowly across the bay. Somewhere, someone was beginning their day with purpose and direction. I was beginning mine with a question still ahead of me.

That felt honest. That felt like enough.

¿Y si me suelto? What if I let go?

I hold the question open. But I am willing to find out.

Note. Spanish-language passages were generated using Google Translate (Google, n.d.) and subsequently reviewed and refined by the author. Any remaining infelicities reflect the limits of machine translation rather than intent.

References

Brown, B. (2010). The gifts of imperfection: Let go of who you think you are supposed to be and embrace who you are. Hazelden Publishing.

Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behaviour in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999

Google. (n.d.). Google Translate. https://translate.google.com

Google. (2026). Day Eight: ¿Y Si Me Suelto? [AI-generated image]. Gemini. https://gemini.google.com

Porges, S. W. (2022). Polyvagal safety: Attachment, communication, self-regulation. W. W. Norton & Company.