A Scholarly Personal Narrative of Attention, Interoception, and Embodied Knowing

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, 2026

Today, it rained in Loreto, and then the rain paused. In that pause, I carried my research materials to the poolside cabana, settling beneath the palapa’s thatched roof to continue the work that has become both intellectual inquiry and embodied practice. The sky remained heavy with moisture, grey clouds pressing low over the date palms and bougainvillea that frame this small sanctuary. The air smelled of wet earth and salt from the nearby Sea of Cortez. Water droplets clung to palm fronds, occasionally dislodging to fall with a soft percussion onto the terracotta tiles surrounding the pool.

This moment, seemingly ordinary in its domestic simplicity, exemplifies the core dynamics of

alonetude, the intentional solitude practice I have been documenting throughout this retreat. The pause in the rain created conditions for what Kaplan and Kaplan (1989) developed as

attention restoration, wherein environments characterised by soft fascination, such as natural settings between weather events, allow directed attention to recover from the depletion caused by sustained cognitive effort. Kaplan’s (1995) subsequent theoretical framework formalised these insights into Attention Restoration Theory. Yet what unfolded at the poolside extended beyond simple restoration. It involved the integration of contemplative presence with scholarly work, demonstrating how

embodied knowing, knowledge accessed through somatic awareness and sensory engagement with place, informs and enriches academic inquiry.

Theoretical Positioning

This narrative draws upon several intersecting theoretical frameworks that have shaped both my retreat experience and the scholarly methodology through which I examine it.

Attention Restoration Theory

Attention Restoration Theory (ART), developed by environmental psychologists Rachel Kaplan and Stephen Kaplan (1989; Kaplan, 1995), proposes that natural environments promote psychological restoration through four key characteristics. Table 1 summarises these foundational components.

Table 1

Four Components of Attention Restoration Theory

| Component | Definition |

| Being Away | The sense of psychological distance from routine demands and mental fatigue. Physical distance helps, but conceptual distance (a shift in mental content) is essential. |

| The match between environmental affordances and personal purposes. The setting supports what the person is trying to accomplish and is inclined to do. | The coherence and scope of the environment. The setting must be rich enough to constitute a whole other world that engages the mind and offers exploration opportunities. |

| Fascination | Engaging attention effortlessly through inherently interesting stimuli. ‘Soft fascination’ (clouds, water, rustling leaves) is restorative, unlike ‘hard fascination’ (television, video games). |

| Compatibility | The match between environmental affordances and personal purposes. The setting supports what the person is trying to accomplish and inclined to do. |

Note. Adapted from ‘The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective’ by R. Kaplan and S. Kaplan, 1989, Cambridge University Press, and ‘The Restorative Benefits of Nature: Toward an Integrative Framework’ by S. Kaplan, 1995, Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15(3), pp. 169–182.

The poolside setting during the rain pause embodied these qualities. I experienced being away through physical distance from daily obligations and the conceptual shift from routine to contemplation. The environment provided extent through the visual scope created by the intersection of built and natural elements: the cabana’s shelter, the pool’s reflective surface, the layered palm grove, and the distant sea. Soft fascination emerged from water droplets falling rhythmically, cloud movements across the grey sky, and the gentle sway of palm fronds. Compatibility arose from the alignment between the environment’s quietness and my need for a reflective workspace where scholarly writing could unfold organically.

Interoception and Embodied Awareness

Interoception, defined as the perception of internal bodily sensations, represents another essential framework for understanding this experience (Craig, 2002; Farb et al., 2015). Interoceptive awareness encompasses multiple dimensions, as outlined in Table 2, which summarises the Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness (MAIA) framework developed by Mehling et al. (2012).

Table 2

Six Dimensions of Interoceptive Awareness

| Dimension | Description |

| Noticing | Awareness of bodily sensations such as heartbeat, breathing, temperature changes, and muscle tension. |

| Attention Regulation | The ability to sustain and control attention to bodily sensations during focused awareness. |

| Emotional Awareness | Recognition of connections between physical sensations and emotional states; the embodied dimension of affect. |

| Self-Regulation | Using bodily signals to modulate distress and regulate emotional responses adaptively. |

| Body Listening | Actively attending to the body’s messages about needs, limits, and preferences with curiosity rather than judgment. |

| Trusting | Experiencing bodily signals as reliable and safe sources of information about one’s internal state. |

Note. Adapted from ‘The Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness (MAIA)’ by W. E. Mehling et al., 2012, PLoS ONE, 7(11), Article e48230. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0048230

During the pause in the rain, my practice involved precisely this kind of interoceptive attention. I noticed the cooling sensation of post-rain air against my skin, the subtle shift in breathing as humidity changed, the grounding quality of sitting in stillness while water sounds created ambient texture, and the alignment between my body’s need for contemplative pace and the environment’s invitation to settle. This embodied awareness did more than simply register physical sensations; it provided epistemological access to knowledge that emerges through lived, sensory engagement with place.

Embodied Knowing and Feminist Epistemology

Embodied knowing, as articulated by feminist epistemologists and phenomenological scholars, challenges the Cartesian separation of mind and body by asserting that knowledge emerges through lived, sensory engagement with the world (Alcoff & Potter, 2013; Grosz, 1994; Merleau-Ponty, 1962). This framework recognises that understanding develops through the body’s interactions with material environments, through sensory perception, through movement and stillness, and through the integration of affective and cognitive processes.

Donna Haraway’s (1988) concept of Situated knowledge emphasises that all knowledge is partial and positioned, emerging from particular embodied, historical, and geographical locations.

Sandra Harding’s (1991) standpoint epistemology further argues that those whose knowledge has been marginalised often possess epistemic advantages precisely because they must navigate both dominant and marginalised perspectives. Working beneath the cabana during the rain pause exemplified this embodied epistemology. The knowledge I generated about solitude, attention, and restorative practice emerged from integrating sensory awareness, environmental responsiveness, and intellectual inquiry.

The Lived Moment

I arrived at the pool carrying my laptop, notebook, and the now-familiar blue bag that has become a symbol of my mobile research practice. The thatched palapa roof overhead, traditional in this region of Baja California Sur, provided shelter while maintaining environmental porosity.

Unlike the enclosed rooms where I sometimes work, the cabana offered what I think of as a threshold space, simultaneously within and without, protected yet permeable. Geographer Yi-Fu Tuan’s (1974) work on place and experience illuminates how such spaces shape emotional geography, how our affective responses emerge through the interplay of enclosure and exposure, intimacy and vastness. This liminality, this state of being between enclosed shelter and open exposure, created optimal conditions for the kind of contemplative work that has characterised this retreat.

The pool water, still and translucent in its turquoise containment, reflected the grey sky with perfect clarity. This mirroring created what I think of as visual resonance, wherein landscape features repeat and reinforce each other, generating aesthetic coherence. The concept draws on Anne Whiston Spirn’s (1998) work on landscape as language, particularly her insight that designed and natural environments communicate through legible patterns. The pool’s surface doubled the sky’s presence, making weather visible in two planes simultaneously. Behind the pool, date palms rose in irregular clusters, their shaggy trunks and feathered fronds creating layered textures against the weighted atmosphere. Some palms stood straight and tall, while others leaned at gentle angles, their shapes recording years of wind patterns and growth responses. Pink bougainvillea, vivid even under grey skies, cascaded over the stone wall that marked the property’s boundary, its colour intensified by the moisture-saturated light.

Environmental psychologist Roger Ulrich (1983) demonstrated that visual exposure to nature, particularly environments featuring water and vegetation, produces affective responses that support psychological recovery. His research established that natural settings reduce stress and promote restorative experiences. Sitting beneath the palapa, I experienced this settling as a lived sensation, beyond abstract theory. My shoulders, which had held tension from concentrated morning writing, gradually released. My breathing, which had been shallow during focused work, deepened and steadied. The environmental cues surrounding me, soft sounds, muted colours, and the rhythm of occasional water drops communicated safety and spaciousness.

Integration of Work and Presence

Opening my laptop to continue writing about intentional solitude while inhabiting that very state created a recursive quality to the experience. I was simultaneously living alonetude and documenting it, simultaneously experiencing the present moment and reflecting upon the patterns I have observed across weeks of practice.

This integration exemplifies the methodological strength of Scholarly Personal Narrative (SPN), the approach that frames this entire project, as identified by Nash (2004). SPN honours lived experience as legitimate scholarly data while maintaining intellectual rigour through theoretical grounding and critical reflexivity.

Unlike traditional research methodologies that position the researcher as a detached observer, SPN recognises the researcher as an embodied participant whose personal experience, when properly contextualised within broader theoretical frameworks and social structures, generates valuable knowledge (Ellis & Bochner, 2000; Richardson, 2003).

My work beneath the cabana involved this dual consciousness. I remained attentive to immediate sensory experience, observing the quality of light, the ambient sounds, and the feeling of air against the skin, while simultaneously engaging these observations through conceptual lenses provided by attention theory, neuroscience, and phenomenology.

The work itself flowed differently here than it does in enclosed spaces. Ideas emerged with less forcing, sentences formed more organically, and connections between concepts became visible through a process that felt closer to recognition than construction. Cognitive scientist Douglas Hofstadter (1979) describes creative thinking as pattern recognition across disparate domains, the capacity to perceive structural similarities between seemingly unrelated phenomena. The poolside environment, with its combination of focused containment (the cabana’s defined space) and ambient stimulation (changing light, the sound of water, the movement of palm fronds), created conditions conducive to associative thinking.

The Neuroscience of Pause

Neuroscientific research illuminates what occurs during moments such as this pause between rains. The default mode network (DMN), a collection of brain regions that activate when attention shifts away from external tasks toward internal mental activity, becomes engaged during restful states characterised by environmental softness (Raichle et al., 2001; Buckner et al., 2008). The DMN supports autobiographical memory consolidation, future planning, perspective taking, and the integration of experiences into coherent narratives. Research by Mary Helen Immordino-Yang and colleagues (2009) demonstrates that DMN activation correlates with ethical reasoning, identity formation, and meaning-making processes, suggesting that these seemingly passive moments of mental wandering serve essential psychological functions.

Simultaneously, the salience network, which includes the anterior insula and anterior cingulate cortex, maintains awareness of both internal bodily states and relevant environmental stimuli (Seeley et al., 2007; Menon & Uddin, 2010). This network acts as a switching mechanism, determining which information merits conscious attention and facilitating shifts between externally directed focus and internally oriented awareness. During the rain pause, my experience involved precisely this dynamic balancing. I intermittently attended to my writing, the poolside environment, internal physical sensations, and the flow of ideas, with attention moving fluidly across these domains without the fragmentation that characterises forced multitasking.

Polyvagal Theory and Felt Safety

Polyvagal theory, developed by neuroscientist Stephen Porges (2011), offers another lens for understanding the embodied quality of this experience. Table 3 outlines the three hierarchical autonomic states identified by Porges.

Three Autonomic States in Polyvagal Theory

| Autonomic State | Characteristics and Functions |

| Ventral Vagal (Social Engagement) | Associated with feelings of safety, calm, and social connection. Supports rest, digestion, face-to-face communication, and prosocial behaviour. The nervous system state that enables learning, creativity, and contemplative practice. |

| Sympathetic (Mobilisation) | Involves activation and arousal, preparing the body for action. Supports adaptive responses to challenge through fight-or-flight mechanisms. Becomes problematic when chronically activated without opportunities for recovery. |

| Dorsal Vagal (Immobilisation) | Associated with shutdown, conservation, and disconnection. In extreme cases, produces freeze responses, dissociation, or collapse. Can also support healthy rest and sleep when accessed from a place of safety. |

Note. Adapted from ‘The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-Regulation’ by S. W. Porges, 2011, W. W. Norton & Company.

The poolside environment communicated safety through multiple channels. The shelter of the cabana, the visible boundaries of the space, the absence of threat-relevant stimuli, and the gentle, predictable quality of environmental changes all signalled to my nervous system that it could remain in the ventral vagal state. This physiological settling enabled the quality of presence I experienced, the capacity to remain simultaneously relaxed and attentive, open yet focused. Porges emphasises that felt safety, rather than actual safety alone, determines which autonomic state predominates. The poolside setting provided both objective safety (shelter, containment, predictability) and subjective safety cues (soft sounds, visual beauty, environmental coherence), creating conditions wherein my nervous system could downregulate defensive responses and support contemplative engagement.

Embodied Epistemology in Practice

The knowledge I generated during this working session emerged through bodily engagement with the environment as much as through cognitive analysis. This exemplifies what feminist philosopher Sandra Harding (1991) calls standpoint epistemology, the recognition that all knowledge is situated, emerging from particular bodily, social, and historical locations. My standpoint during this retreat is grounded in specific intersecting positions. I am a white settler-Canadian woman in midlife, a precarious academic worker experiencing career displacement, a mother whose children have launched, a person exploring intentional solitude after years of collective disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, and someone temporarily inhabiting a landscape markedly different from my northern home. Each of these positions shapes what I notice, what feels significant, and how I interpret experience.

The cooling sensation of post-rain air carried particular meaning within this situated context. For someone accustomed to Canadian winters, the idea of cooling being associated with comfort rather than discomfort, with relief rather than challenge, represents a sensory reversal. This embodied knowledge, the visceral understanding that cooling can signal respite, becomes metaphorically resonant when thinking about emotional regulation and the need for periods of reduced intensity following sustained activation.

Similarly, the sound of water, whether falling droplets or the distant murmur of pool filtration systems, activated associations shaped by my geographical origins. Water sounds in northern contexts often signal seasonal transition: the breakup of ice, the rush of spring melt, the first rain after winter’s snow. Here in Loreto, water sounds carry different meanings. They mark the rare gift of precipitation in an arid landscape, the maintenance of human-created oases, the intersection of scarcity and abundance. These layered meanings, emerging from the meeting of personal history with present place, constitute situated knowledge, knowledge that acknowledges rather than erases its specificity (Haraway, 1988).

The Pause as Practice

Pausing, the deliberate slowing or temporary halting of activity, represents a practice often devalued within cultures of productivity and constant engagement. Sociologist Judy Wajcman (2014) analyses how temporal acceleration characterises contemporary life, with technologies promising efficiency paradoxically generating experiences of time scarcity and rushed consciousness. Against this backdrop, the choice to pause, to sit at the poolside rather than pushing through the work in an enclosed room, constitutes a minor but meaningful resistance to the imperative toward continuous productivity.

The poet and essayist Mary Oliver (2008) writes that attention is the beginning of devotion, suggesting that how we direct awareness reflects what we value and shapes what becomes possible. During the rain pause, I devoted attention to the integration of scholarly work with embodied presence, to the practice of remaining with complexity rather than rushing toward resolution, to the capacity to hold multiple modes of awareness simultaneously. This practice of pause differs from complete cessation. I continued working, but the quality of that work changed within the poolside environment. Ideas emerged with less striving, prose flowed with greater ease, and the relationship between effort and ease was better balanced.

Contemplative scholar Pico Iyer (2014) observes that in an age of acceleration, nothing can be more exhilarating than going slow, and in an age of distraction, nothing is so luxurious as paying attention. The rain pause created conditions for this luxurious attention, through environmental support for sustained awareness rather than forced focus. The threshold space of the cabana invited presence without demanding performance. The sensory richness of the setting engaged attention gently, providing sufficient stimulation to prevent mind-wandering into rumination while maintaining sufficient spaciousness to allow creative association.

Reflection and Integration

As the afternoon progressed, the pause in the rain eventually ended. Moisture began falling again, first as sporadic drops, then as steady precipitation that pattered rhythmically against the palapa thatch. I remained at work beneath the shelter, the sound of rain creating an acoustic texture that enhanced rather than disrupted concentration. This transition from pause to rain illustrates what philosopher Gaston Bachelard (1964) describes as intimate immensity: the experience of feeling both enclosed and connected to vastness, protected within a small shelter while remaining in relationship with larger atmospheric forces.

The hours spent at the poolside cabana generated multiple forms of knowledge. There was the intellectual work captured in written prose, the development of arguments and the articulation of frameworks. There was the somatic knowledge gained through embodied presence, the visceral understanding of how the environment shapes consciousness and how intentional positioning within space influences the quality of attention. There was the methodological insight into how Scholarly Personal Narrative functions and how personal experience, when rigorously attended to and theoretically contextualised, contributes to scholarly discourse.

Perhaps most significantly, there was the experiential confirmation that alonetude, as I have been theorising and practising it throughout this retreat, represents a learnable skill rather than an innate capacity. The ability to inhabit solitude with presence, to maintain attentiveness without anxiety, to hold steadiness amid transition (such as the shift from rain to pause to rain again), emerges through repeated practice within supportive environments. The poolside cabana offered such an environment. Its combination of shelter and openness, containment and permeability, created conditions wherein contemplative presence could deepen.

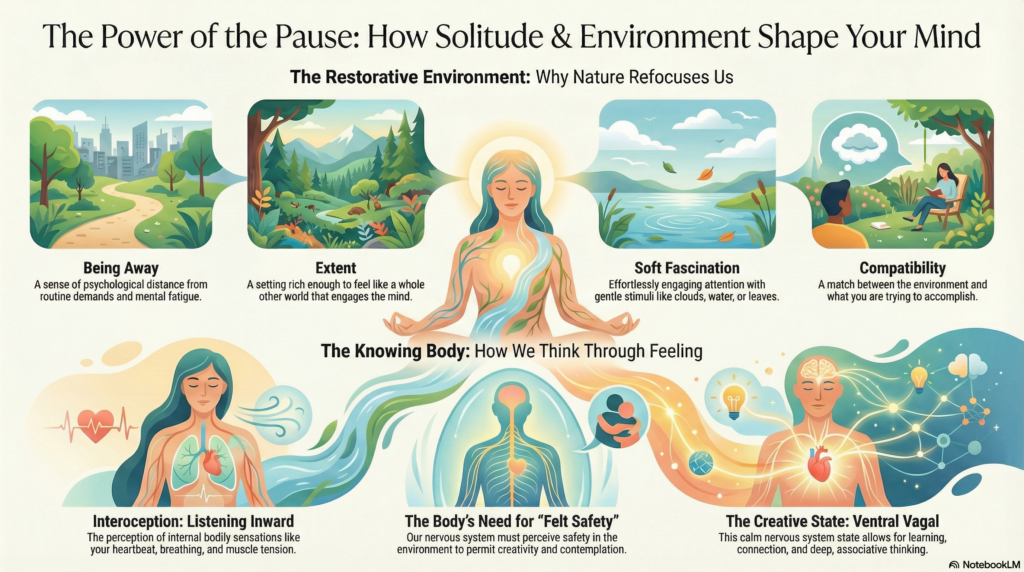

The Power of the Pause: How Solitude and Environment Shape Your Mind

Photo Credit: Notebook LM, 2026

Pause

The pause between rains, seemingly a minor meteorological event, created a doorway into a deeper understanding of how attention, environment, and embodied presence interrelate. Working beneath the palapa during that pause allowed me to experience directly what I have been theorising abstractly throughout this project. Alonetude, the intentional inhabiting of solitude, characterised by volition, presence, meaning, and felt safety, flourishes within environments that support rather than overwhelm attention, that invite rather than demand, that hold space for both focused work and wandering awareness.

This narrative represents one moment within a larger investigation, yet it captures the essence of what I have been learning. Knowledge emerges through the body as much as through the mind. Environment shapes consciousness in ways both subtle and profound. Pausing, rather than representing weakness or waste, constitutes a necessary practice for sustained creativity and well-being. And scholarly inquiry needs to diminish lived experience to generate insight. Instead, when personal narrative is properly grounded in theory and critically examined, it contributes meaningfully to academic discourse while remaining accessible to readers seeking practical guidance.

The rain eventually stopped completely, leaving the landscape refreshed and the air sweetened with ozone. I closed my laptop as the afternoon shifted toward evening, having produced both written work and experiential knowledge. The poolside cabana, with its threshold position between shelter and exposure, had held space for integration, for the meeting of intellectual inquiry and embodied practice. Tomorrow it may rain again, and I will likely return to this same spot, continuing the practice of alonetude, continuing the work of paying attention, continuing to discover what becomes possible when we pause long enough to truly inhabit the present moment.

References

Alcoff, L., & Potter, E. (Eds.). (2013). Feminist epistemologies. Routledge.

Bachelard, G. (1964). The poetics of space (M. Jolas, Trans.). Orion Press. (Original work published 1958)

Buckner, R. L., Andrews-Hanna, J. R., & Schacter, D. L. (2008). The brain’s default network: Anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1124(1), 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1440.011

Craig, A. D. (2002). How do you feel? Interoception: The sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 3(8), 655–666. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn894

Ellis, C., & Bochner, A. P. (2000). Autoethnography, personal narrative, reflexivity: Researcher as subject. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 733–768). Sage.

Farb, N. A. S., Daubenmier, J., Price, C. J., Gard, T., Kerr, C., Dunn, B. D., Klein, A. C., Paulus, M. P., & Mehling, W. E. (2015). Interoception, contemplative practice, and health. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, Article 763. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00763

Grosz, E. (1994). Volatile bodies: Toward a corporeal feminism. Indiana University Press.

Haraway, D. (1988). Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3), 575–599. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066

Harding, S. (1991). Whose science? Whose knowledge? Thinking from women’s lives. Cornell University Press.

Hofstadter, D. R. (1979). Gödel, Escher, Bach: An eternal golden braid. Basic Books.

Immordino-Yang, M. H., McColl, A., Damasio, H., & Damasio, A. (2009). Neural correlates of admiration and compassion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(19), 8021–8026. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0810363106

Iyer, P. (2014). The art of stillness: Adventures in going nowhere. TED Books/Simon & Schuster.

Kaplan, R., & Kaplan, S. (1989). The experience of nature: A psychological perspective. Cambridge University Press.

Kaplan, S. (1995). The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15(3), 169–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-4944(95)90001-2

Mehling, W. E., Gopisetty, V., Daubenmier, J., Price, C. J., Hecht, F. M., & Stewart, A. (2009). Body awareness: Construct and self-report measures. PLoS ONE, 4(5), Article e5614. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0005614

Mehling, W. E., Price, C., Daubenmier, J. J., Acree, M., Bartmess, E., & Stewart, A. (2012). The Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness (MAIA). PLoS ONE, 7(11), Article e48230. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0048230

Menon, V., & Uddin, L. Q. (2010). Saliency, switching, attention and control: A network model of insula function. Brain Structure and Function, 214(5–6), 655–667. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-010-0262-0

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1962). Phenomenology of perception (C. Smith, Trans.). Routledge. (Original work published 1945)

Nash, R. J. (2004). Liberating scholarly writing: The power of personal narrative. Teachers College Press.

Oliver, M. (2008). Red bird. Beacon Press.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. W. W. Norton & Company.

Raichle, M. E., MacLeod, A. M., Snyder, A. Z., Powers, W. J., Gusnard, D. A., & Shulman, G. L. (2001). A default mode of brain function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 98(2), 676–682. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.98.2.676

Richardson, L. (2003). Writing: A method of inquiry. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 923–948). Sage.

Seeley, W. W., Menon, V., Schatzberg, A. F., Keller, J., Glover, G. H., Kenna, H., Reiss, A. L., & Greicius, M. D. (2007). Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. Journal of Neuroscience, 27(9), 2349–2356. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5587-06.2007

Spirn, A. W. (1998). The language of landscape. Yale University Press.

Tuan, Y.-F. (1974). Topophilia: A study of environmental perception, attitudes, and values. Prentice-Hall.

Ulrich, R. S. (1983). Aesthetic and affective response to natural environment. In I. Altman & J. F. Wohlwill (Eds.), Human behaviour and environment: Advances in theory and research (Vol. 6, pp. 85–125). Plenum Press.

Wajcman, J. (2015). Pressed for time: The acceleration of life in digital capitalism. University of Chicago Press.