Silence as a Place

I have been here one week now, and something has changed in my relationship with silence.

For the first several days, silence felt like an absence: the absence of traffic, of notifications, of the constant hum of obligation that had become the background noise of my life. I noticed silence the way one notices a missing tooth, by the shape of what was gone. The quiet felt strange, almost suspicious, as though it were hiding something.

This morning, sitting on the small balcony with coffee cooling in my hands, I realised that silence had become something else entirely. It had become a place. A place I could enter. A place I could inhabit. A place that held me rather than something I had to hold at bay.

The Pause Before the Storm

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, 2026

Silence as Autonomous Presence

The Swiss philosopher Max Picard (1948/1988), in his remarkable book The World of Silence, offers language for what I am experiencing. Picard argues that silence is neither void nor absence but rather an autonomous phenomenon: a presence that exists independently of speech and sound, a reality that begins beyond the falling away of noise.

Silence as Substance

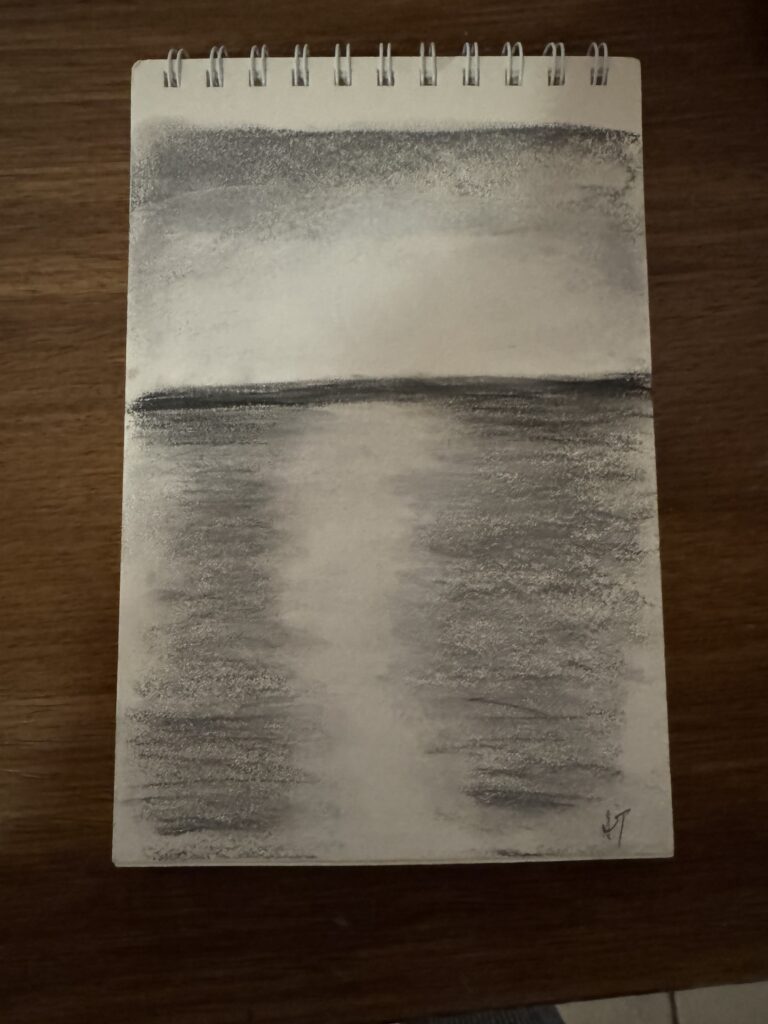

Charcoal Sketch: Amy Tucker, 2026

When language ceases, silence begins. But it begins for reasons beyond the ceasing of language. The absence of language simply makes the presence of silence more apparent.

Picard, 1948/1988, p. 15

This distinction matters. If silence were merely the cessation of sound, it would be defined entirely by what it lacks. It would be a negative space, an emptiness awaiting filling. But Picard insists that silence has substance, has being, has its own formative power. Silence, in his account, shapes human beings just as language shapes us, though in different ways.

Silence as Autonomous Phenomenon

When Picard describes silence as autonomous, he means that silence exists independently of human will or action. We uncover silence already present beneath the words. Silence, in this framework, is primary. Language emerges from silence and returns to it. The words we speak are like waves rising from and falling back into a vast sea of quiet that preceded them and will outlast them.

Bench, Waiting…

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, 2026

Learning to Enter

I have spent much of my adult life in noisy environments: classrooms full of voices, offices humming with machines, homes filled with the sounds of family and obligation. Silence, when it appeared, felt like an interruption rather than a foundation. I filled it quickly, almost reflexively, with music, with podcasts, with the radio playing in the background while I worked. The thought of sustained quiet made me uneasy in ways I left unexamined.

Now I understand that unease differently. What I was avoiding in silence was an encounter. Silence waits. It listens. Picard writes that where silence is, we are observed by silence. Silence looks at us more than we look at it. This is precisely what felt threatening: the sense that in silence, I would have to meet myself without distraction, without the buffer of activity and noise that kept me safely busy.

Here in Loreto, I am learning to enter silence rather than escape it. The learning has been gradual. In the first days, I noticed how quickly my mind rushed to fill the quiet. Thoughts formed into lists. Conversations from months ago replayed themselves. The body responded with tension, as though silence required vigilance, as though something might be hiding in the stillness.

Staying silent requires patience. Rather than filling it, I began to notice its texture. Silence, I discovered, carries layers. There are distant sounds within it: the far-off call of a bird, the whisper of wind, the rhythmic breathing of the sea. Silence holds space rather than collapsing inward. Over time, it revealed rhythm.

Silence Has a Rhythm

Breath of the Canopy

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, 2026

This has been the week’s revelation: silence is alive.

The sea rises and falls. Wind moves through the palm fronds in waves that sound like breathing. My own breath creates a gentle cadence if I stay still enough to notice. Even the light shifts in patterns that feel rhythmic, the slow arc of morning into afternoon into evening. Silence contains all of this motion. It lives. It moves. It pulses with a life I had been too busy to perceive.

Picard understood this. He wrote of the forest as a great reservoir of silence from which quiet trickles in a thin, slow stream, filling the air with its brightness. The image is precise: silence as source, as reservoir, as something that flows rather than simply exists. Here by the Sea of Cortez, the silence flows from the water, from the mountains, from the vast expanse of sky that has no interest in human schedules or human noise.

Table 1

Qualities of Inhabited Silence

| Hunger, fatigue, and contentment become perceptible without distraction | What It Means | How It Manifests |

| Autonomous | Silence exists independently of human will or speech | Silence is uncovered rather than created; it precedes and outlasts words |

| Layered | Silence contains subtle sounds, movements, textures within it | Wind, breath, distant birds, the sea: silence holds rather than excludes |

| Rhythmic | Silence has patterns, cycles, flows | Morning quiet differs from evening quiet; silence moves with time |

| Companionable | Silence accompanies without demanding; it witnesses without judging | A sense of being held, of belonging without performance |

| Silence has patterns, cycles, and flows | Silence allows internal signals to surface; it reduces interpretive load | Hunger, fatigue, contentment become perceptible without distraction |

Note. The framework synthesises Picard (1948/1988), contemplative traditions, and personal observation. These qualities emerged through sustained attention rather than analysis.

Inhabited Silence

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, 2026

After years shaped by disruption, urgency, and collective strain, silence offers what I had needed without knowing it: relief from constant interpretation.

In my working life, I was perpetually reading: reading student papers, reading institutional policies, reading the room in meetings, reading the unspoken tensions in corridors and committee gatherings. Every moment required assessment, response, and performance of understanding. Even leisure hummed with demand; podcasts, news, and social media all called me to process, evaluate, and react.

Silence asks for none of this. There is no need to respond. There is no performance required. Experience can simply exist without commentary. This permission feels revolutionary after decades of cognitive labour.

In silence, listening shifts from sound to sensation. From external cues to internal signals. Hunger is evident when no distraction overrides it. Fatigue makes itself known without shame. Contentment arises unannounced, without having to justify itself against productivity metrics.

Silence clarifies.

Silence and the Settling Body

The connection between silence and nervous system regulation is becoming clearer to me now. Yesterday, I wrote about the body beginning to remember safety. Today, I understand that silence is part of how that remembering happens.

Stephen Porges (2022) describes how the autonomic nervous system responds to environmental cues, constantly scanning for signals of safety or threat. Chronic noise, whether literal sound or the metaphorical noise of constant demand, keeps the system in a state of vigilance. The body cannot fully settle when it must remain alert to incoming information that might require a response.

Silence provides what Deb Dana (2020) might call a cue of safety. In the absence of demands, the nervous system can begin to downregulate. Muscles soften. Breath deepens. The hypervigilance that felt like normal alertness manifests as chronic tension, and that tension begins to subside.

I have noticed this in my own body over the past week. Each quiet morning reinforces the message that stillness can be supportive. Each evening without urgent input confirms that the world holds steady even when I am unreachable. The body learns through repetition, and silence provides the conditions for that learning.

When Silence Becomes Companionable

Perhaps the most unexpected discovery of this week is that silence can be companionable.

Held Without Asking

Credit: Amy Tucker, 2026

I arrived here expecting solitude to feel lonely, at least sometimes. I expected to miss conversation, to feel the absence of other voices. And there have been moments of longing, particularly in the evenings when the day’s warmth fades, and the darkness feels vast. But alongside that longing, something else has emerged: a sense of being accompanied by silence itself.

This is difficult to articulate without sounding more mystical than I mean. I mean something quite practical: that silence holds without judgment. It asks nothing of me in terms of interest, productivity, or usefulness. It holds my worth independent of output. Silence simply is, and in its presence, I am permitted to simply be.

Picard writes that when two people are conversing, a third is always present: silence is listening. I have begun to feel this even when alone. Silence listens to my thoughts without needing me to speak them. It witnesses my morning rituals, my wanderings to the water, and my afternoon rest. It accompanies without intruding.

Belonging within silence feels different than belonging through interaction. It carries steadiness rather than affirmation. It arises from alignment rather than exchange.

The Noise We Carry

One Missed Call

Photo Credit: Amy Tucker, 2026

Picard wrote his meditation on silence in 1948, and even then, he worried about what he called the world of noise encroaching on human consciousness. He wrote of radio noise as something that surrounds us, accompanies us, and creates a false sense of continuity that substitutes for genuine presence. If he found the mid-twentieth century noisy, I can only imagine what he would make of our current moment.

We carry noise with us now. It lives in our pockets, vibrates against our bodies, follows us into bedrooms and bathrooms and the last quiet corners of our lives. The smartphone has colonised silence more thoroughly than any technology before it. There is no longer any space, Picard wrote presciently, in which it is possible to be silent, for space has all been occupied now in advance.

Coming here required a deliberate choice to leave that noise behind. I brought my phone but set it to silent. I check email once a day, if that. I have no television, no radio, no podcasts playing while I walk. The withdrawal was initially uncomfortable, as with any withdrawal. The hand reached for the device reflexively. The mind generated reasons to check, to see, to know what was happening elsewhere.

Now, a week in, the reaching has slowed. The mind has settled into the rhythm of this place rather than the rhythm of the feed. Silence has expanded to fill the space that noise once occupied. And I am beginning to understand that this space was never empty. It was always full of silence, waiting for me to notice.

A Somatic Record

The somatic log continues to reveal patterns. Day seven marks the emergence of what I can only call ease with silence, a comfort in quiet that was absent at the beginning of the retreat.

Table 2

Somatic Log: Day 7

| Time | Observation |

| Morning | Woke without alarm. Silence felt welcoming rather than empty. Sat with coffee in quiet for forty minutes without restlessness. Breath deep and steady. VV state. |

| Midday | Walked to water in silence. No impulse to fill quiet with podcast or music. Noticed layers within silence: wind, birds, waves. Felt companioned rather than alone. |

| Evening | Watched sunset in complete quiet. Silence felt like a place I could inhabit rather than endure. Body soft, jaw relaxed, shoulders down. Gratitude present. |

| VV sustained throughout the day. Silence is experienced as a supportive presence rather than an absence. |

Note. VV = ventral vagal state. The emergence of silence as a companionable practice marks a qualitative shift from earlier periods.

Silence and Alonetude

I am beginning to understand that silence is one of the essential conditions for alonetude: the intentional, contemplative solitude I came here to practice. Without silence, solitude risks becoming merely physical isolation, a removal from others that leaves the inner noise intact. With silence, solitude opens into something spacious enough to hold reflection, restoration, and the slow work of becoming present to oneself.

Silence creates the conditions for attention to turn inward. It reduces the load of constant input that normally occupies cognitive and emotional resources. It allows the nervous system to settle, the body to soften, the mind to stop its endless scanning for threat or opportunity. In silence, energy conserves itself. Presence becomes possible.

This is why retreat centres and monasteries have always understood silence as discipline rather than deprivation. Silence asks to be inhabited rather than endured. Silence is itself the somewhere, the place where transformation becomes possible because we are finally still enough to receive it.

Evening, Day Seven

The sun is setting as I write this. The sky over the Sea of Cortez has turned the colour of ripe peaches, fading to lavender at the edges. The mountains across the water are silhouettes now, their details absorbed into the growing dark.

It is very quiet.

Quiet, mostly. I can hear the water lapping against the shore. A bird calls somewhere in the distance. My own breath moves in and out, marking time. But beneath and around these sounds, silence holds. Silence is the medium through which everything else moves, the space in which sound becomes possible.

Picard writes that silence contains everything within itself. It is always wholly present and completely fills the space in which it appears. I feel this now, sitting in the fading light. Silence asks nothing of me. It holds no anticipation of my next word or my next action. It simply holds, vast and patient and present.

One week ago, I arrived here full of noise: the noise of years of overwork, of worry, of the constant chatter of a mind that had forgotten how to be still. The noise is quieter now. It remains, and perhaps it always will. But silence has made room for itself within me, as it does this evening, surrounding and holding the small sounds of life without being diminished by them.

Silence is a place. I am learning to live here.

References

Dana, D. (2020). Polyvagal exercises for safety and connection: 50 client-centred practices. W. W. Norton & Company.

Picard, M. (1988). The world of silence (S. Godman, Trans.). Gateway Editions. (Original work published 1948)

Porges, S. W. (2022). Polyvagal theory: A science of safety. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 16, Article 871227. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnint.2022.871227

Silence as place rather than absence is the phenomenological core of this entry, resonating with Bachelard's (1964) concept of inhabited space: silence becomes a room one can enter and dwell in. This is alonetude at its most concentrated — the capacity to be, in Winnicott's (1958) phrase, alone in the presence of the world without anxiety. The sea as acoustic environment contributes what Kaplan and Kaplan (1989) call fascination: the quality of an environment that holds attention without effort and allows the mind to rest.