Arrival is the doorway through which everything else enters.

Artist Statement

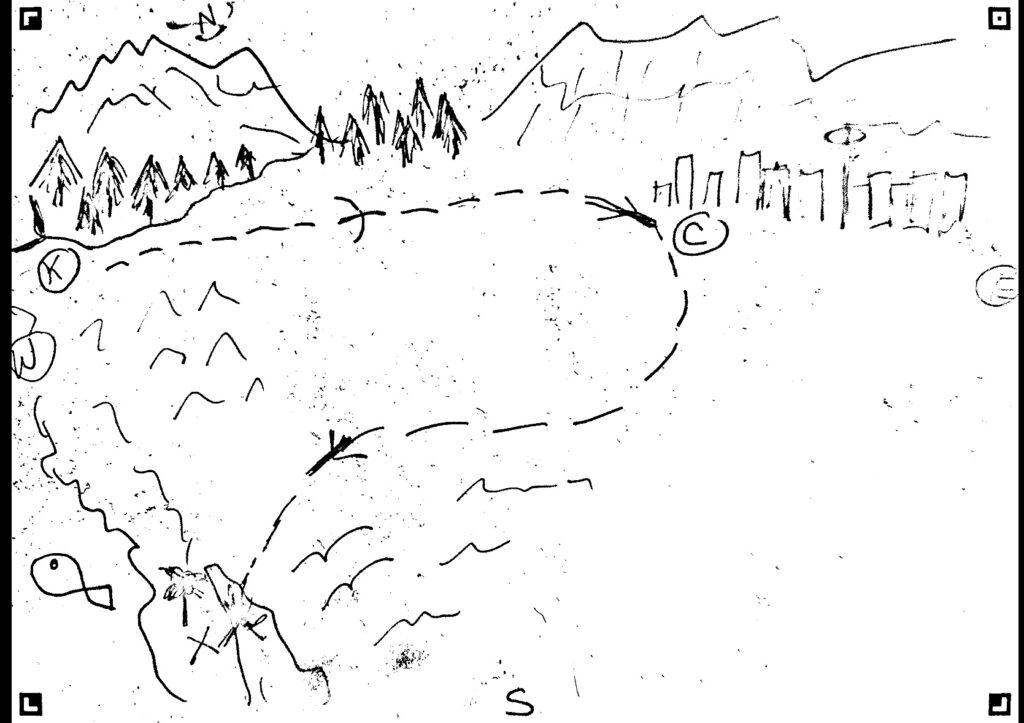

This one came through quickly.

Unplanned. Unscripted. I drew it the way thoughts sometimes arrive when the body is tired but the mind is still moving. Lines first. Meaning later.

At first glance, it looks almost childlike. Loose marks. Unsteady figures. A pathway that curves without precision. Mountains on one side. Water on the other. Small symbols scattered across the space as if they surfaced faster than I could organise them.

But when I sat with it longer, I realised it was mapping something internal rather than geographical.

The road runs down the centre. Winding. Circuitous. It bends, loops, redirects. There are arrows that suggest movement but without certainty. It is a path that is being negotiated rather than followed.

On one side, there are figures and shapes that feel relational. Animals. Faces. Presences that suggest companionship, memory, or watchfulness. On the other side, sharper lines. Mountains. Edges. Terrain that feels more solitary, more effortful to cross.

There is even a small structure near the end of the path. Almost like a village, or a place of arrival. Yet it carries no detail. It sits lightly on the page, more suggestion than destination.

What strikes me most is the openness of the centre space. So much white. So much unfilled terrain.

It feels honest.

This drawing makes no claim to the whole route. It records movement in progress. The way journeys are often held internally before they become visible externally.

It reminds me that mapping is rarely about accuracy. Sometimes it is about witnessing where you are in the moment you draw the line.

Photo Credit Amy Tucker, January 2026

The plane descended over mountains I had only imagined. Below, the Sea of Cortez stretched turquoise and still, the body of water that Jacques Cousteau famously called the world’s aquarium (Pulitzer Centre, 2023). The desert rose glowed golden behind it, ancient and patient. I had come alone, deliberately, to a place where silence would be allowed to remain.

The flight attendant announced our arrival in two languages, but I barely heard her. My body had already begun the quieter work of landing. I noticed my shoulders softening, my breath slowing, the steady thrum of anticipation giving way to something gentler. Arrival, I would learn, begins before the wheels touch ground.

Where Desert Meets Sea

Loreto sits at the edge of two worlds. To the east, the Sea of Cortez stretches toward the Mexican mainland, its waters teeming with nearly 900 species of fish and 32 types of marine mammals (PanAmerican World, 2018). To the west, the Sierra de la Giganta rises abruptly from the desert floor, granite and volcanic rock shaped by millennia, holding canyons and ancient springs in its folds. This is a landscape of stark beauty, where the desert’s dry heat meets the sea’s salt-laden air.

This place carries layers of history that I was only beginning to understand on arrival. On October 25, 1697, the Jesuit missionary Juan María de Salvatierra founded the Misión de Nuestra Señora de Loreto Conchó at an Indigenous settlement called Conchó, home to the Monquí people (Misión de Nuestra Señora de Loreto Conchó, 2025). It became the first permanent Spanish mission on the Baja California peninsula. It served as the administrative capital of both Baja and Alta California for more than a century. The town’s motto still reads: “Loreto: Cabeza y Madre de las Misiones de las Californias,” which translates to “Head and Mother of the Missions of the Californias.”

Before the missions arrived, Indigenous peoples had inhabited this peninsula for thousands of years. The Cochimí lived in the central regions to the north, their rock art still visible in the Sierra de San Francisco, with paintings carbon-dated to over seven thousand years before present (Kuyimá Ecotourism, 2025). These were semi-nomadic peoples who moved with the rhythms of the desert and sea, living in small family bands that travelled seasonally in search of water, edible plants, and game (Cochimí, 2025). To the south lived the Guaycura and the Pericú. European diseases and colonial disruption would decimate these populations within a few generations, and by the nineteenth century, the Cochimí language had become extinct (Laylander, 2000; Indigenous Mexico, 2024). Their memory endures in archaeological sites and oral history, a reminder that the land I walked upon held stories far older than my own.

I arrived without consciously carrying this history. It was only later, walking the malecón, the seafront promenade, in the evening light, that I began to understand why this place felt layered. Silence here seemed to hold more than absence. It held memory.

Title: The History of Time

Artist Statement

I almost missed it.

It sat quietly among the other stones, indistinguishable at first glance. Just another fragment in a shoreline made of fragments. It was only when I bent down, slowed my gaze, that the spiral revealed itself.

Perfectly held inside the rock.

A fossil. A record of life that once moved through water long before my own footsteps ever reached this shore. What struck me was its patience, more than its age. The way it had remained intact while everything around it had eroded, shifted, broken down into smaller pieces.

Time was visible here.

As compression. As density. As felt weight. Layers folded inward. Motion turned into memory. The spiral itself felt symbolic, but I resisted making it symbolic too quickly. Instead, I stayed with its material presence. Its texture. Its quiet persistence.

Holding this image, I thought about how many histories live beneath our feet without announcement. How much survives without spectacle. The fossil requires no demand. It waits for recognition.

There is humility in that.

It reminded me that archives take many forms beyond the written. Some are geological. Somatic. Embedded in landscapes that remember what human timelines often forget.

I left it there.

It felt important that it remain where it was found. Still held by the shoreline. Still in conversation with water, weather, and time.

Sometimes witnessing is enough.

Photo Credit Amy Tucker, January 2026

Why I Came Alone

Before I left, people asked whether I was nervous about travelling alone. Whether I was running from something or toward it. Whether thirty days was too long or too short. I had no clean answers.

What I knew was simpler: I was tired in ways that sleep alone could never reach. After years of institutional pressure, caregiving across generations, and the collective exhaustion that followed the pandemic, my nervous system had forgotten how to settle. Stillness felt dangerous. Silence felt loud. Being alone had become entangled with being abandoned, and I had lost the ability to tell the difference.

I came to Loreto to learn how to be with myself again. To practise what I have come to call alonetude, a term I use to describe the intentional, generative space between solitude and loneliness. I define alonetude as an enduring contemplative orientation toward chosen solitude, characterised by intentionality, presence, meaning, and a sense of safety. It is a posture of chosen presence with oneself, distinct from both the pain of loneliness and the mere fact of being physically alone.

Researchers have long distinguished between solitude and loneliness. Loneliness, understood as the painful gap between desired and actual social connection, persists even in crowds (Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2010). As Nguyen (2024) describes, it is an experience of perceived isolation characterised by unmet expectations in social relationships. Solitude, by contrast, can be volitional, meaning chosen or self-determined, and restorative, meaning it supports recovery and wellbeing. Research shows that when individuals autonomously decide how to spend their solitary time, they experience more positive emotions and lower stress (Nguyen et al., 2018). The key distinction lies in motivation: self-determined solitude occurs when a person spends time alone to gain emotional benefits or engage in meaningful activities, whereas non-self-determined solitude happens when aloneness is imposed by circumstance or social exclusion (Nguyen et al., 2024).

Somewhere between those poles lies the quieter possibility I was seeking: the decision to remain present with oneself, without urgency or escape. And so I chose a place where the sea would be my witness and the mountains my backdrop. A place with enough history to remind me I was small, and enough stillness to let that smallness feel like relief.

Title: My Space

Artist Statement

It was the stillness that met me first.

Quiet, contained, that only temporary rooms seem to hold. The bed was made with precision. Pillows aligned. A folded throw placed carefully across the centre as if anticipating arrival before I had even stepped inside.

I remember standing in the doorway for a moment longer than necessary.

There is always something disorienting about entering a space that is prepared for you, a stranger to itself. A room that offers comfort without history. Function without attachment. It asks nothing, but it also holds nothing of you yet.

My suitcase rested against the wall. Half-unpacked. A visible reminder that I was both arriving and already preparing, in some distant way, to leave.

The mirror reflected me back into the frame of the room. Researcher. Traveller. Body in transition. The image felt less like documentation and more like evidence of in-betweenness. Neither fully settled nor unsettled. Simply passing through.

What drew me most was the order.

Clean lines. Neutral tones. A controlled environment that contrasted with the emotional complexity I had carried with me. In that contrast, I felt a subtle recalibration begin. The nervous system recognising safety through predictability. Through the ordinary rituals of placing belongings, arranging clothing, setting a journal on the bedside table.

Temporary spaces can be profoundly instructive.

They remind us how little is required to begin again each day. A bed. A window. A place to write. A place to rest the body between movements.

Nothing extravagant. Just enough.

I let the room be what it was. I let it remain neutral. Let the relationship form slowly. Presence before imprint.

It was never meant to be mine.

Only to hold me for a while.

Photo Credit Amy Tucker, January 2026

The First Hours

At the small airport, the air hit me first. Dry and warm, carrying salt and something mineral. January in British Columbia had been grey and wet; here, the sky stretched blue without apology. I collected my bag and stepped outside. No one was waiting.

That fact landed differently than I expected. There was relief in it. No negotiation, no performance, no need to translate my fatigue into something legible for others. I hailed a taxi and watched the desert roll past the window. Cardon cacti stood like sentinels along the road, their arms raised to the sky. Smaller plants hugged the ground, adapted to scarcity.

When I arrived at my small casa, I sat with my bags still packed. I sat on the edge of the bed. I noticed the texture of the light coming through the shutters. I noticed my shoulders drop. I saw the impulse to fill the silence, to check messages, to plan, to narrate the moment to someone far away, and I let the impulse pass.

This is the work of arrival: resisting the urge to fill the space you have just entered immediately. Allowing the body to land before the mind begins its commentary. Trusting that orientation will come without forcing it.

I opened the windows. Outside, I could hear unfamiliar birds. The sea was close and visible from where I sat. I drank water slowly. I let the room remain unfinished around me.

Title: Morning Views

Artist Statement

I kept returning to this balcony without meaning to. It became a quiet threshold in my days, a place suspended between inside and outside, between the life I carried with me and the landscape that asked nothing in return.

In the mornings, I would step onto the cool tiles barefoot, still half inside sleep. The body would register the air, the light, the slow movement of the palms before my mind began its usual work of organising and anticipating. I came to value that order. Sensation first. Thought later.

There was no spectacle here. Just rhythm. Wind moving through the trees. The horizon holding steady. Light arriving gradually across sand and railing. Nothing hurried me. Nothing required interpretation. I could stand at the edge of the day without performing readiness for it.

Over time, this space became orienting. Internally, rather than geographically. I stood here without writing or planning. I stood, breathed, and allowed myself to arrive slowly. The thatched roof overhead offered shelter, while the open railing kept me connected to the wider world. Protected, yet open.

It reminded me that solitude often lives in these in-between spaces. Places where one can look outward while staying grounded inward. Places where presence is enough.

This balcony was never dramatic. That is why it mattered. It held me quietly as each day began.

Photo Credit Amy Tucker, January 2026

Listening to the Body

That evening, I walked to the water. The malecón curved along the shore, lined with benches and the quiet activity of a small town at dusk. Pelicans floated in loose formations offshore. The light turned gold, then amber, then something closer to rose.

Title: All in a Line

Artist Statement

They were already gathered when I arrived.

A line of pelicans along the shoreline, facing the water as if the horizon had called them into formation. I stood back and watched. What held me was the pace of it, more than the scene itself. No urgency. No competition. Just bodies resting in proximity, each one holding its place without needing to claim it.

I noticed how easily they occupied stillness.

Waiting, unhurried. Together, without entanglement. The sea moved behind them in long, steady breaths, and I felt my own body begin to match that rhythm. In that moment, I was witnessing something, I was witnessing a posture. A way of being that measured nothing.

I stayed back.

Distance felt right. I stayed where I was, letting the scene remain intact. Watching them, I felt reminded that presence rarely requires action. Sometimes it is enough to stand at the edge of things, attentive, unhurried, and willing to belong to the pause.

Photo Credit Amy Tucker, January 2026

I found a bench and sat. I had no book, no phone in hand, no task. Just the sound of water lapping against stone and the slow parade of families walking after dinner. A child ran past laughing. A couple held hands. An older man fished from the rocks nearby, patient and unhurried.

The body knows arrival before the mind catches up. It registers safety in the loosening of the jaw, the deepening of breath, the release of tension held so long it had become invisible. Stephen Porges (2011), in his foundational work on polyvagal theory, explains that the autonomic nervous system continuously scans for cues of safety or danger through a process he calls neuroception. This term refers to the neural evaluation of risk and safety that occurs below conscious awareness, reflexively triggering shifts in physiological state (Porges, 2022). Unlike perception, which involves mindful awareness, neuroception operates automatically, distinguishing environmental features that are safe, dangerous, or life-threatening.

When the nervous system detects sufficient cues of safety, what Porges (2022) describes as a neuroception of safety, the body shifts from states of protection into states of restoration. The ventral vagal complex, a branch of the vagus nerve associated with calm, connection, and social engagement, becomes activated. This shift arrives below conscious choice. It is something we allow by creating conditions where safety can emerge.

Sitting there on that bench, watching the pelicans dive and the light change, I felt something unclench. Quietly, almost imperceptibly. The vigilance I had carried for years began, very slowly, to set itself down.

Arrival creates conditions for this shift. By slowing down. By resisting the impulse to perform or produce. By letting the first hours remain unstructured. When nothing is demanded, the nervous system begins to trust the moment.

An Invitation

Arrival, I learned that first evening, is a threshold. It marks the movement from one way of being into another. Thresholds resist rushing. When crossed too quickly, they close before anything has time to change.

You can practise arriving anywhere. It can happen in a parked car before going inside. In a quiet kitchen after everyone has gone to bed. In the first moments of waking, before you reach for your phone. These small arrivals matter. Research suggests that even brief periods of self-selected solitude can foster relaxation and reduce stress (Nguyen et al., 2018).

Wherever you are reading these words, I offer this as an invitation. Let yourself arrive here. Notice the surface beneath you. Notice your breath. Let the moment widen without needing it to mean something yet.

Arrival offers orientation before transformation. It offers orientation. The chance to acknowledge where you are, physically, emotionally, internally, before asking yourself to be anywhere else.

That first night in Loreto, I fell asleep to the sound of distant waves. The room was still unpacked. The days ahead were unplanned. And for the first time in longer than I could remember, that openness felt like permission rather than a threat.

Llegada. Arrival. The doorway through which everything else enters.

The Sea of Cortez, Loreto, Mexico

Artist Statement

The light arrived before I was ready for it.

I stepped outside and the sky was already holding colour, soft pinks moving slowly across the horizon, settling into the edges of the clouds as if the day were being introduced rather than announced. The palms moved in the wind, with weathered resilience, gently,. They bent without breaking. They have done this many times before.

I stood there longer than I planned to.

Watching the movement of the trees, the stillness of the sand, the quiet line where water meets land. What held me was the atmosphere of endurance, alongside the beauty. Nothing here was rushing. Even the wind felt patient. I noticed how my body responded, how my breathing slowed without instruction.

In that moment, I felt accompanied without needing company.

The landscape asked nothing of me. It simply allowed me to arrive as I was, tired, reflective, present. Standing there, I understood that rest arrives in many forms beyond full stopping. Sometimes it comes from witnessing something that knows how to keep standing, even in constant wind.

Photo Credit Amy Tucker, January 2026

References

Cochimí. (2025, November 22). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cochimí

Google. (n.d.). Google Translate. https://translate.google.com

Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioural Medicine, 40(2), 218–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8

Indigenous Mexico. (2024, September 4). Indigenous Baja California: The rarest of the rare. https://www.indigenousmexico.org/articles/indigenous-baja-california-the-rarest-of-the-rare

Kuyimá Ecotourism. (2025, August 24). The Cochimí: Indigenous tribe of Baja California Sur. https://www.kuyima.com/cochimi-indigenous-tribe/

Laylander, D. (2000). The linguistic prehistory of Baja California. In D. Laylander & J. D. Moore (Eds.), The prehistory of Baja California: Advances in the archaeology of the forgotten peninsula (pp. 1–94). University Press of Florida.

Misión de Nuestra Señora de Loreto Conchó. (2025, February 7). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Misión_de_Nuestra_Señora_de_Loreto_Conchó

Nguyen, T.-V. T. (2024). Deconstructing solitude and its links to well-being. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 18(11), Article e70020. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.70020

Nguyen, T.-V. T., Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2018). Solitude as an approach to affective self-regulation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 44(1), 92–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167217733073

PanAmerican World. (2018, November 21). Sea of Cortez: The world’s aquarium. https://panamericanworld.com/en/magazine/travel-and-culture/sea-of-cortez-the-worlds-aquarium/

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. W. W. Norton & Company.

Porges, S. W. (2022). Polyvagal theory: A science of safety. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 16, Article 871227. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnint.2022.871227

Pulitzer Centre. (2023). Mexico: Emptying the world’s aquarium. https://pulitzercenter.org/projects/sea-of-cortez-aquaculture-ocean-fish-farming-global-market

Note. Spanish-language passages were generated using Google Translate (Google, n.d.) and subsequently reviewed and refined by the author. Any remaining infelicities reflect the limits of machine translation rather than intent.

Arrival at Loreto enacts what van Gennep (1960) calls the threshold crossing of a rite of passage: the moment of separation from the previous structure is complete, and the liminal phase begins. The wonder recorded here — the shock of a different sensory world — corresponds to what Kaplan and Kaplan (1989) term restorative experience: environments that require involuntary attention and allow directed attention to recover. Writing bilingually at this moment is itself a methodological choice: language as a site of embodied knowledge.